A number of Australian conservators have encountered problematic glassine-like repairs on paper-based items. While many such repairs can be removed easily with aqueous methods, others resist removal. Either the adhesive used for the repairs is a water-resistant formulation, or changes over time (within the adhesive, with the substrate or with some other material) have caused it to become insoluble. Removing old unsightly repairs made with the material has been very difficult.

Appearance

The repair papers are typically translucent (a little cloudy, like tracing paper; not entirely clear or transparent) and yellowed. The adhesive is generally also yellowed but still also translucent. Sometimes brush strokes are visible; sometimes the adhesive layer is not easily visible at all. The width of repair strips and patches varies. It’s possible some repairs are “home-made” and others are commerical products.

Age

The age of the repairs is unknown (and probably varies). Collection material on which the repairs have been found date from late 19th century ephemera (State Library of Victoria) and post-1957 drawings from Yirrkala (State Library of NSW). The repairs could have been applied at any time.

Home-made

Some repairs appear homemade, or at least not pre-glued – there are visible brushstrokes and repair strips or patches are not of consistent width.

Commercial products

It’s possible some repairs are made with commercial products. A number of patents exist for gummed papers, which may or may not have been used to make commercial products. Many of the formulations describe could result in non-water-soluble bonds. Some patent examples:

- US patent 2,125,241, 1938, Mid-States Gummed Paper Co, ‘Gummed paper product’: Adhesive material described as dextrine, starch, animal glue or a combination, applied as a thin layer to one side of paper. Powdered animal glue applied as a second layer over the first.

- US patent 2,143,600, 1939, Mid-States Gummed Paper Co, ‘Gummed tape’: one strip of paper with a layer of water-soluble gum is attached to a strip of latex-impreganted paper with a layer of rubber cement.

- US patent 2,167,629, 1939, Stein + Hall Manufacturing Company, ‘Method of applying gummed tape, labels, and the like’: uses ‘incompletely dextrinised’ starch and often adds urea. Saturated borax solution used to remoisten the adhesive. May also add animal glue, casein, natural gums and natural or synthetic resins.

- US patent 2,793,966, 1957, Nashua Corporation, ‘Non-curling gummed paper’: mixes very fine particles of primary adhesive into a solution of a second adhesive. E.g. ground dextrin added to polyvinyl methyl ether in toluol. Other adhesives which may be used include animal glue, carboxy methyl cellulose, vinyl methyl ether-maleic anhydride. Both gums must be water soluble but the second adhesive must be soluble in a solvent in which the primary adhesive is not.

- US patent 2,917,396, 1959, Dennison Manufacturing Company, ‘Flat gummed paper’: a water-activatable ‘gum’ is dissolved in water and dispersed in a water-soluble ‘resinous binder’ that has been dissolved in a solvent (e.g. toluene). Examples: polyvinyl methyl ether + toluene + animal glue; N-butyl amine salt of polyvinyl acetate-maleic anhydride copolymer + toluene + animal glue.

- US patent 2,976,178, 1961, Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company: Paper is coated with a layer containing polyacrylic acid and two types of dextrin. Two classes of dextrines used: those highly soluble in water and exhibiting very low viscosity, and those that are relatively insoluble in water (usually highly branched).

- US patent 3,202,539, 1965, The Brown-Bridge Mills Inc, ‘Non-curling gummed paper’: Powdered water-soluble glue is dispersed in a binder ‘relatively insensitive to changing humidity’. Suggests a wide range of material combinations – examples: dextrin or animal glue as the water-soluble adhesive and rosin, shellac, PVA, polyhydric alcohol (Sorbitol) and/or polyvinyl methyl ether-maleic anhdyride as the binder. Notes that many combinations will become water-resistant after initial activiation.

- US patent 3,212,924, 1965, Dennison Manufacturing Company, ‘Non-curling gummed paper’: Water-activatable gum is dispersed in a water-insoluble binder (dissolved in a solvent). The ‘gum’ used in example formulations was always a mixture of animal glue and dextrin. The binder may be a polyvinyl ester copolymer, polyvinyl chloride, butadiene-styrene copolymers, or water-insoluble polymers of acrylic esters.

Treatment

Attempts at removal easily results in skinning of the surface of the object. Hot water or steam has sometimes aided removal, especially if the surface of the repair paper is abraded prior to treatment to aid wetting.

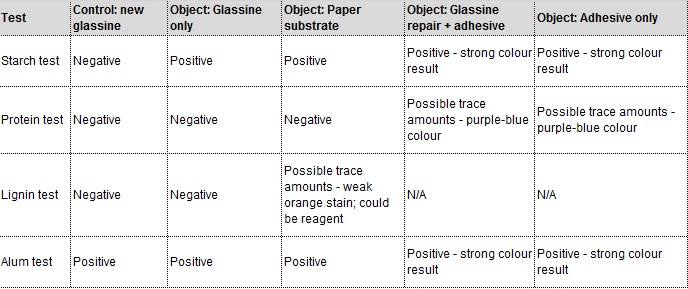

Case study – State Library of Victoria, 2014

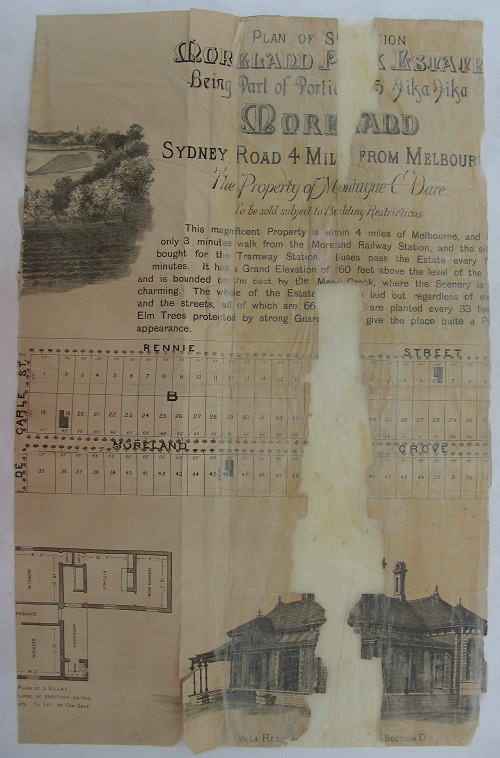

Sample: large glassine-like repair applied over loss on Melbourne sub-division plan (see image).

Chemical spot tests: the glassine repair paper (without adhesive), the plan and the adhesive on the glassine repair all tested positive for starch and alum (the adhesive strongly so). Both the papers tested (glassine repair and object substrate) were negative for protein, though the adhesive may contain trace amounts. The plan paper also contain lignin but the reaction was not strong. (See table)

Solubility tests (2014): a number of solvents were tested for their ability to wet out/swell the glassine repair, including deionised water (room temperature; hot; boiling; steam), ethanol, 50:50 ethanol/deionised water, methyl cellulose poultice, toluene, tri-ammonium citrate, and EDTA (bath; Phytagel poultice). Chelating agents were included in the hopes that alum detected using spot tests might be bound up by the chelating agents. None of the treatments showed any advantage over deionised water, which was not particularly effective in the first place.

FTIR (MV): ATR-FTIR analysis of sample (May 2015) was a good match with spectra for wheat starch and rice flour. Possible protein peak at 1530 & 1630cm-1. (Operating conditions: 4000-400cm-1, res 4cm-1, 32 scans).

Contributors

Alice Cannon*, Albertine Hamilton, Marika Kocsis, Jane Hinwood, Sarah Bunn, Stephanie Baily