In June 2019, the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) hosted a four-day intensive workshop to examine in detail the management of time-based media artworks in collections. The first day included a public symposium, which offered a larger number of interested professionals an overview of some of the key points of this challenging topic. The following workshop then included delegates from ten institutions from across Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong and speakers from the AGNSW, Tate Time-Based Media Conservation team and State Library of New South Wales.

Symposium panel: Justin Paton, AGNSW; Carolyn Murphy, AGNSW; Bernice Murphy, Curator; Agatha Gothe-Snape, Artist; Daniel von Sturmer, Artist; Louise Lawson, Tate; Stephen Jones, Technician. Photo credit: Jenni Carter

One of the most refreshing aspects of this workshop was that it purposefully brought together museum professionals from across conservation, curatorial, registration and technician roles. The management and care of time-based media artworks relies on all these roles and requires us all to rethink what we do and how we work together.

In the spirit of the workshop, this article includes responses from several of these perspectives and seeks to share some of the learnings across our professions. We look forward to continuing to build and share a common understanding and approach to the care of time-based media artworks in Australasian collections.

Lucy Clark, Registrar, Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney

As the title of the workshop infers, flexibility is key.

Time-based artworks by their very nature are not fixed or static; for the AGNSW the defining feature of these works is duration.

For Registrars used to documenting and cataloguing the physical thing, the object that was acquired, these works prompt many questions and challenge us to think about ways to document variability / replaceability / or (sometimes) a thing that does not yet exist.

What is the work?

How do we track and locate the various components—both physical and virtual?

What is going on display?

What status should the hard-drive have—is it the artwork or just a carrier of content?

Thankfully, others have asked these questions too and come up with frameworks that help address these documentation quandaries and allow for a standardised approach.

For AGNSW, this questioning led to a conceptual rethinking of how time-based artworks were documented. In their revised approach, the artwork is catalogued to reflect everything that is required for the work to be displayed. Therefore, a digital component is recorded as a ‘temporary file’ with a standardised description noting ‘created for display’ which allows for an exhibition copy to be created and located each time the work goes on display. Other variable items, which may need to be sourced for each installation, are also recorded as a separate part with a standardised description: ‘to be sourced’.

Different record types and status allow for the creation of non-work of art (NWA) records to describe dedicated or stock equipment required to show the work and master/working versions of the time-based media components. These are all related and linked to the main artwork record, again allowing these components to be tracked and located and ensuring a true picture of everything that needs to be maintained or sourced in order to display and preserve the work into the future.

Examples from AGNSW and the Tate illustrated how this level of detail and clarity in documentation at the point of acquisition plays an essential part in informing requirements and resourcing for future loans or internal displays of the works. While there will be nuances within each institution, these frameworks provide a useful starting point for us all to review and adapt our standards and approach to account for the needs of these works.

Kasi Albert, Conservator, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney

Developing approaches to the conservation of time-based art is an activity that challenges and expands the parameters of the profession. Attention is brought firmly back to culture, context and meaning and requires a reframing of conventional conservation goals. It is therefore critical to engage with other conservators and colleagues in allied specialisations. This workshop provided an unprecedented opportunity to do this in a dedicated and supportive environment. The field is complex and continually improving, even for well-established practitioners like the Tate. However, there were a few key points, which seemed to be critical for all conservators who were becoming involved in the conservation of time-based art.

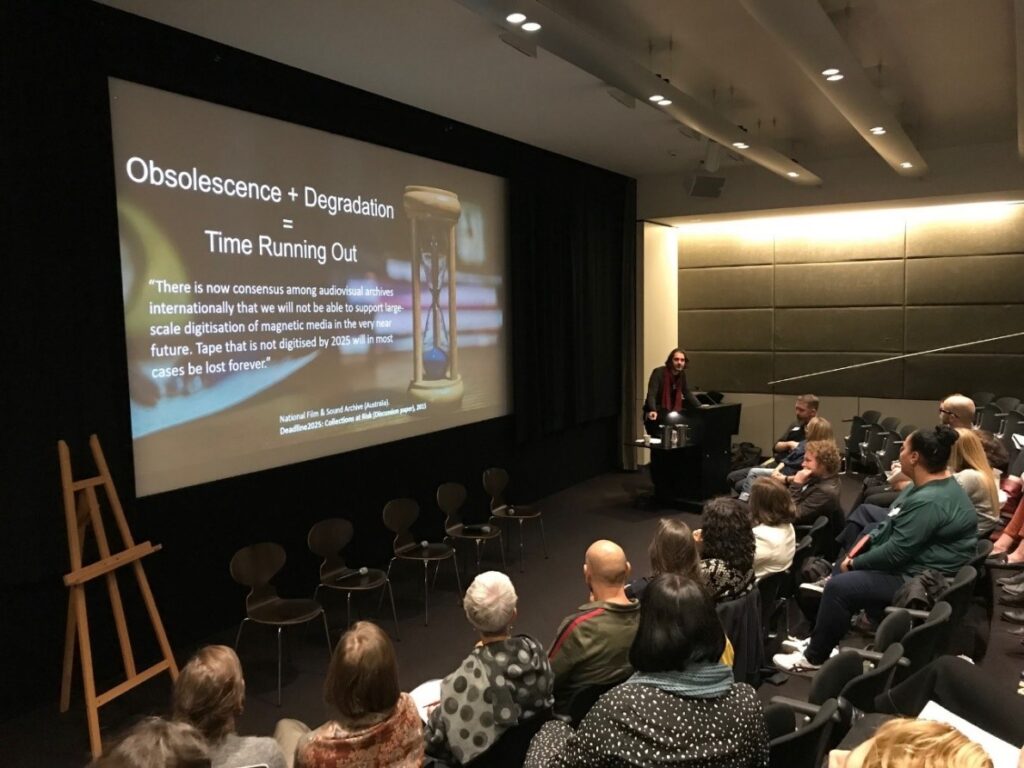

Audio preservation presentation: Damien Cassidy, State Library NSW. Photo credit: Asti Sherring

The first was the importance of organisational support for growing and strengthening processes and perceptions around the needs of time-based art. This is not a role that can be successful in isolation, as it requires input and cooperation from many different stakeholders. It also likely requires the conservator to build on their existing practical knowledge, as artworks may involve technology with which they are not familiar. While the technicians remain the experts in operating and troubleshooting equipment and tech, it’s incredibly useful for the conservator to have a general understanding of both analogue and digital technologies.

Another significant element is the use of documentation as a direct and constructive tool for conservation of artworks, which may often have components that are ephemeral or difficult to define. Collection surveys will help to define the scope and nature of time-based art collection holdings and may help to direct decision-making for priorities. Condition reporting can assist in identifying needs and resources required for acquisition or display of works, meaning conservators can more effectively communicate to other stakeholders what is realistically needed to ensure appropriate and long-term preservation of all aspects of a time-based artwork. Finally, overarching documents like installation guides, artist questionnaires and iteration reports provide invaluable intersections for information both practical and conceptual. Unlike more ‘traditional artworks’ (paintings, sculptures, etc.), without these accompanying records, time-based artworks often exist in a precarious position between loss and preservation.

On a personal level, a final benefit of this workshop was that it provided a reminder of the breadth and variety of specialist knowledge and different points of view that are relevant in this area. Learning from and applying the approaches of other experts only serves to enrich and enhance the conservation profession.

Scot Cotterell, Manager—Time-Based Media, Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart

‘Towards a Flexible Future’ created a potent, pertinent and highly valuable focus to work through and discuss the many complexities involved in the care and maintenance of time-based artworks.

The attendee structure—requiring two participants from each organisation—seeded collaboration before the event even occurred. The hybrid of public program, symposium, workshop and the addition of a facilitated creative development session at EY meant that formats and presentation modes shifted throughout the four days, mirroring the diversity of the kinds of cultural practices and works we are seeking to better understand and care for.

Subject matter and speaker diversity was also well considered and provided significant breadth from key organisational expertise across the GLAM sector, allowing tangents, connections, practices and viewpoints from differing physical, social, cultural and resourcing backgrounds that should help attendees to adapt and scale practices as we all travel back to our respective institutions to advocate for TBA. The generosity of our host organisation and all the participants created a rigorous and collegial framework, robust conversation and candour that will enable future information and resource sharing.

Technical information and processes, often the most expansive and nebulous aspect of time-based art delivery and preservation, was addressed in an integrated way through various viewpoints and discussions. The rapidity of change inherent in time-based media artworks and the need for integration and consideration of this trait into existing collection management, curatorial, display and documentation practices was the core theme. The need for this integration to be discursive and adaptive in an informed and consultative way in a system open to new inputs and knowledge, guided by existing conservation frameworks emerges for me as the core thrust of the conference.

AGNSW staff supporting contemporary artist panel: Lisa Catt, Charm Watts, Stuart Montgomery, Asti Sherring, Jake van Dugeteren. Artwork: Robert Andrews, A Connective Reveal – Language. Photo Credit: Rebecca Barnott-Clement

Ongoing challenges we collectively face that emerged were: resources: access to time, money and infrastructure; time: institutional and individual, and staff to perform work, digitisation, conservation, migration, reporting; risk: environmental, entropic, systemic, unforeseen and medium-specific; fragility: the changing nature of art practice, the rapidity of technology change, dissociation; communication: formats, languages, processes, departments, databases.

Often this mix of challenges presents institutionally as insurmountable, difficult, expensive and fraught. ‘Towards a Flexible Future’ allowed the time and space to consider many granular, interconnected and evolving aspects of this field while encouraging us to start now, where we are, and with what we have available to us.

‘There is only one way to eat an elephant: one bite at a time.’