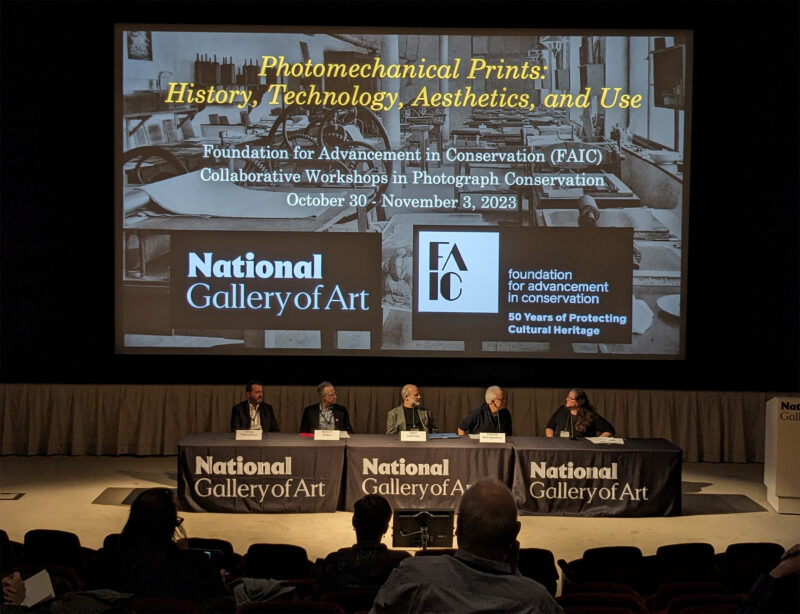

In October–November this year, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) hosted a five-day symposium focused on photomechanical prints. Born from the need for mass-production, permanence and technical control, photomechanical printing translates and transforms photographs and other imaging techniques. Photomechanical images are ubiquitous, yet we tend not to notice their daily presence—when we see images in books and magazines, or on postcards and cereal packets, terms like rotogravure, heliotype or half-tone, don’t, for most of us, immediately spring to mind. Elizabeth Gralton, Leandra Flores and Emma Dacey, recent graduates of the Cultural Materials Conservation master’s degree at the University of Melbourne, travelled to DC to learn more about photomechanical image-making. Below is a summary of our learning and impressions gained during the week.

Monday:

We attended a tour of the National Gallery of Art, where curators from the Rare Books, Image Collections, and Prints and Drawings departments provided a glimpse of photomechanical items from their collections. The Rare Books department holds a significant collection of publications regarding the procedures of various photomechanical processes, many of which are viewable online. An exhibition of select titles introduced us to some technical manuals and treatises on the qualities of photomechanical printing. The Image Collections team provided hands-on examination of photomechanical techniques including photogravure prints and printing plates, collotypes, photolithographs and half-tone prints. In addition, the Prints and Drawings curators provided examples of photomechanical prints in modern and contemporary artworks. We also had a guided viewing of an exhibition mounted to complement the symposium, Etched by Light: Photogravures from the Collection, 1840–1940.

Tour of the Image Collections, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Tuesday–Thursday:

Three days of presentations provided a multidisciplinary examination of photomechanical prints, their place in collections, their material processes and aesthetic values, and their social and historical significance. We heard from artists, curators, historians, collectors and conservators. These perspectives provided insights into how and why photomechanical prints are made, their relation to the history of photography and printing developments, how they have been historically valued or dismissed as an imaging process and art form, and what they can reveal about the context in which they were created and used.

Attitudes towards photomechanical printing, and its place in the history of art making, was a key theme to emerge over the course of the symposium. Photomechanical printing processes were developed to overcome some of the limitations of photographs at the time: lack of permanency, the cost and time involved in reproduction, and inability to be printed in one streamlined process along with text. Because of their position at the intersection of photography and printmaking, photomechanical prints have tended not to enjoy the status of either. As demonstrated by Geoffrey Belknap, in spite of their ample representation in collections, scant attention has been paid to photomechanical printing in the historiography of photography. The expectation to faithfully reproduce an existing image ostensibly divorces the photomechanical process from the creative process of either the photographer or the artist. Paradoxically though, as highlighted by Rebecca Capua, the difficulty of achieving accurate reproductions and the technical skills required by printmakers to achieve good results has led to photomechanical processes being derided as not objective enough.

As we learned, at any one of the many steps of any given photomechanical process, innumerable variables contribute to the final aesthetic. Presentations by contemporary practitioners of historical techniques, including Jon Goodman (photogravure), Barret Oliver (Woodburytype) and Craig Zammiello (direct gravure) demonstrated the magnitude of factors to be controlled when seeking an artistic outcome. This preoccupation with the artistic potential of photomechanical printing has historical precedents: other papers demonstrated that practitioners such as Edouard Baldus (presentation by Kate Addleman-Frankel), Ernest Edwards (by Julie Melby) and Ansel Adams (by Dr Anne Hammond) were concerned with technical mastery in service of artistic interpretation rather than mere identical reproduction. In other contexts, accurate reproduction has been a key objective: Jane Brown’s presentation demonstrated the importance of the University of Melbourne’s collection of photomechanical prints for students of art so far removed from the centres of Western art production.

Historical attitudes and uses, and issues of authenticity and subjectivity of photomechanical printing were major themes to emerge from the conference. Presentations outlined how the malleability and accessibility of photomechanical prints has been applied socially, including in postcards created during revolution in Iran (Mira Xenia Schwerda), illustrations of race (Robyn Phillips-Pendleton) and manipulated depictions of female faces (Prof. Gerry Beegan). Other papers highlighted the technical issues and innovators whose experiments paved the way to printing processes as we know them today: Martin Jürgens described rare early prints created by etching daguerreotypes to create intaglio reproductions; Steven Joseph and David Hanson illuminated the earliest developers of half-tone printing screens; and Dr Carina Parraman stretched our understanding with her explanation of contemporary printing practices using RGB pigments.

From a conservation perspective, a pertinent and challenging question that recurred throughout the presentations was about language and identification. In part because of their technical complexity, terminology associated with photomechanical processes has been notoriously difficult to pin down. Over time, imperatives to commercialise similar processes being developed concurrently and in multiple countries led to a proliferation of names for very similar techniques. Several presentations sought to clarify the language we use to talk about processes. Of particular note was Benjamin Levy’s presentation on photographic half-tone in which he proposed a clear framework for applying terminology for each step of the photomechanical creation process.

There were 28 presentations in total, too many to touch on here—hopefully a volume of post-prints will result from this symposium, allowing further dissemination of research, which will help us all to be more precise in our characterisation and understanding of photomechanical prints.

A discussion panel at the Photomechanical Prints symposium, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Friday:

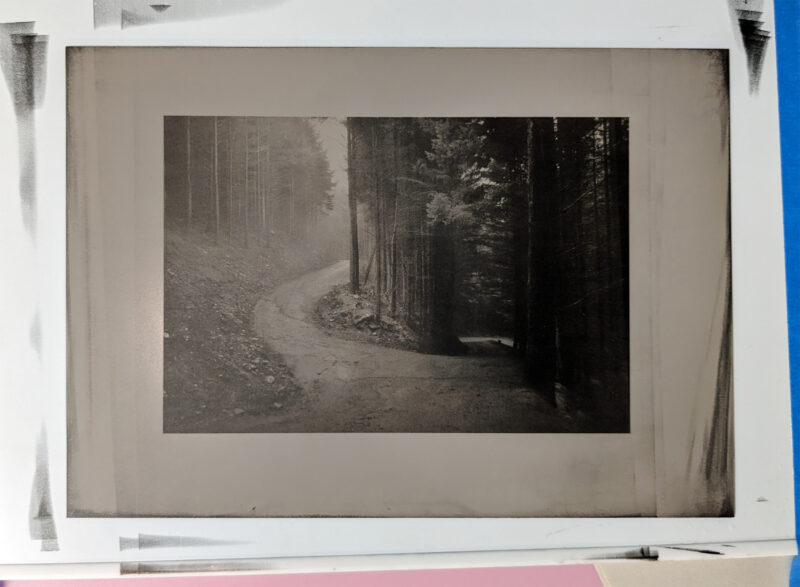

At the conclusion of the symposium, we had the opportunity to get our hands inky. Elizabeth attended a photogravure workshop taught by Jon Goodman, where the group observed the transfer of a photographic image to a gelatine-coated copper plate and the subsequent etching process before inking up some of Jon’s plates and pulling prints to take home.

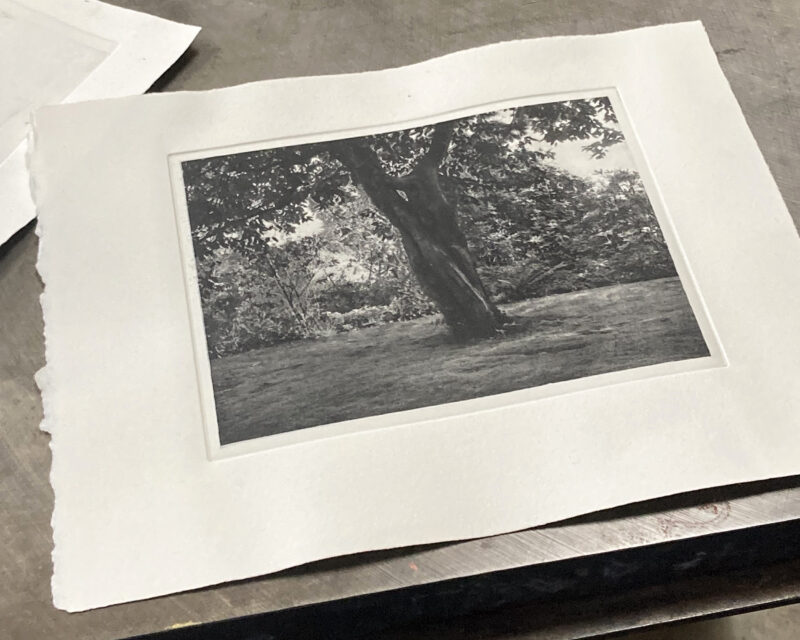

Emma attended a collotype workshop with Benrido Collotype Academy’s Master Printer, Osamu Yamamoto. Founded in 1887 and based in Kyoto, Benrido is considered one of the last collotype printing workshops in the world. We were shown how to prepare a collotype plate and ink it ready for printing. Each participant was able to pull numerous prints and experience the subtlety and elusiveness of the tactile skills and attention to the materials necessary to produce a successful collotype. Benrido Collotype Academy offers workshops in Kyoto; view their website for more details.

A collotype plate inked and ready for printing.

A photogravure print pulled during the workshop.

Elizabeth Gralton is the Sherman Fairchild Postgraduate Fellow specialising in works on paper at the Thaw Conservation Center, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Elizabeth’s attendance at the symposium was supported financially by the Sherman Fairchild Foundation.

Leandra Flores is a conservator of paper and books. Leandra is currently employed by the United States National Archives and Records Administration, and the Seattle Art Museum.

Emma Dacey is a conservator of photographs and works on paper, currently working in Naarm/Melbourne at the University of Melbourne and the Royal Children’s Hospital Archives. Emma was awarded the FAIC/Mellon Photograph Workshop Professional Development Scholarship to support her attendance at the symposium.

Elizabeth, Emma and Leandra in Washington, DC.