On 17 April this year we lost a man who can rightly be called the “Father of the Conservation Profession in Australia”. The AICCM and its membership owe much to Colin; he was there at the establishment of the organisation and was always a highly involved member, serving as National President for a time, and being awarded the first Conservator of the Year award in 1995. Colin could always be counted on to ask a difficult question about AICCM finances from the floor at an AICCM AGM.

First among any list of Colin’s achievements would be the 24 years he ran the Materials Conservation course at the CCAE (later the University of Canberra). Colin was appointed the head of the program on its establishment in 1978 and remained there for 24 years. Over that time the course produced 338 graduates who went on to populate the public and private conservation laboratories of the country.

To this growing band of professional conservators Colin was friend, mentor, teacher, researcher, disseminator, author, colleague, advocate and exemplar. He helped bring Australian conservation into the modern era and insisted that it be taken seriously; conservation in Australia became a discipline, a profession, a calling.

What follows is an obituary for Colin prepared by his close friend and colleague Dr Jan Lyall. Jan completed the CCAE Materials Conservation course and during her career was head of Conservation at the National Library of Australia, established the National Preservation Office at the National Library of Australia and in 2000 established the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World National Committee, of which she was chair until 2012.

Obituary for Colin Pearson – Father of the Conservation Profession in Australia

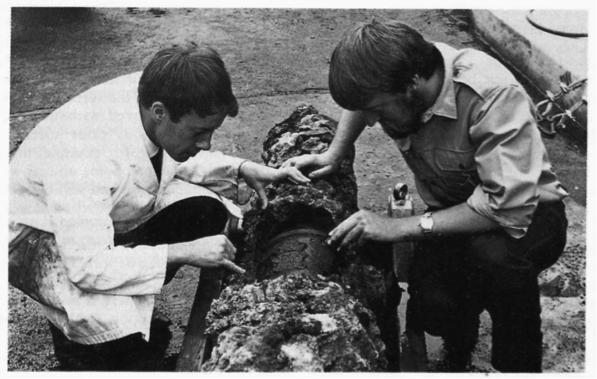

Colin Pearson was born on 20 January 1941 in the English Midlands where he was also educated. He came to Australia in 1967 on a three-year contract to work at the Defence Standards Laboratory in Maribyrnong in the Corrosion Science Department. He had recently graduated with a PhD from the Manchester Institute of Science and Technology, specialising in corrosion science. The turning point in his career came in January 1969 when he received a phone call from the Receiver of Wrecks in Queensland asking for assistance in how to deal with the 6 recently discovered cannon and the cast iron ballast jettisoned by Lieutenant James Cook from the H.M.B. Endeavour in 1770. Colin jumped at the opportunity to work on such nationally significant material. Prior to his work on the Cook material Colin was unfamiliar with the conservation profession, but the experience was an epiphany and set him on a path he would follow for the rest of his professional life.

The successful treatment of the cannon was published in the international journal Nature, and for his work Colin was awarded the MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) in 1970. This publicity drew national and international attention to Colin and to the field of conservation. At this time Colin had not yet turned 30.

After his three years in Melbourne Colin’s contract was up and in 1970 he returned briefly to the UK. Keen to pursue a career in conservation he submitted an application for a position as Head of Conservation at the Birmingham Museum.

Prior to departing Australia Colin had been approached by David Ride, Director of the Western Australian (WA) Museum, seeking his interest in setting up a conservation laboratory in the WA Museum. In 1971, a firm offer was made and Colin accepted; he was keen to pursue his new passion and keen to return to Australia. There was a minor issue with his appointment; there was no conservation position offering an appropriate salary for someone with Colin’s reputation and qualifications. He was therefore appointed as Curator of Meteorites, with the added responsibility of running the conservation department. He did both but spent more time in conservation.

The Conservation Department of the WA Museum in Fremantle specialised in the treatment of maritime archaeological material from Dutch and colonial shipwrecks on the WA coast. Colin remained Director for 7 years during which he established a professional conservation laboratory with trained staff. His research work during that time embraced metals, a variety of marine archaeological materials, waterlogged wood, ceramics, rock art and disaster planning. His appointment at curatorial level gave conservation greater status than was the case elsewhere in the country and it also gave Colin an insight into the best way of relating to museum curators. The fact that Colin was a trained PhD, with the success of the Cook relics behind him, gave him and the WA Museum a degree of credibility that was lacking elsewhere. The surge in growth of the WA Conservation department over the next 7 years can be attributed to several factors: strong support of David Ride; the establishment of the Whitlam Government with an interest in heritage; and Colin’s ability to recruit excellent staff.

In the early 1970s Conservation in Australia was in its fledgling stage – very few people were even aware that it was a profession and there were fewer than 10 professionally qualified conservators in the country. As a general rule their pay was appalling, working conditions were abysmal and there was no professional organisation to represent them. Meanwhile the many important public and private collections in the country were at risk through neglect and active deterioration.

However awareness of the problem was growing, one key reason being a UNESCO sponsored study conducted in 1970 to examine the conservation of cultural property in Australia and Papua New Guinea. This study was conducted by Dr Anthony (Tony) Werner the then Keeper of the British Museum Research Laboratory.

Following on from this study, in 1973 Colin organised the first national conservation seminar in Perth, the aim of which was assessing the problems affecting cultural material in Australia and the resources available for combatting these problems. The meeting was supported by grants from the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, the Australia National Commission for UNESCO, the Australian Academy of the Humanities and the Trustees of the Western Australian Museum. It was during this meeting that the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material (AICCM) was established with Colin elected as its inaugural president. He later was appointed Honorary Professional Life Member (1991) and in 1995 was presented with the AICCM Inaugural Conservator of the Year award. In 2014 Colin established a grant attached to the AICCM – Outstanding Research in the Field of Material Conservation Award.

The next major event to influence the history of conservation in Australia, and Colin’s role in it, was the establishment by the Whitlam Government in April 1974 of a committee of inquiry on museums and national collections chaired by P.H. Pigott. It was tasked with examining a range of issues, including how to improve collection and conservation facilities for national material, with particular attention to research needs and training. The recommendations relating to conservation in this comprehensive study – forever known as the Pigott Report – were largely based on the recommendations from the earlier UNESCO study. They included a recommendation that a training program be established at the Canberra College of Advanced Education (CCAE). Sadly, the report was submitted just before the sacking of the Whitlam Government and implementation of the recommendations was delayed – in some cases no action ever resulted. The report itself can be viewed at: http://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/1269/Museums_in_Australia_1975_Pigott_Report.pdf

However, with a good deal of behind-the-scenes politicking and lobbying by influential people, including Professor John Mulvaney who was a member of the Pigott inquiry, the first Australian course in Materials Conservation was established at the CCAE at the end of 1977 with a commencement date of March 1978. Colin was appointed to run the program and so began his career as an educator.

However, with a good deal of behind-the-scenes politicking and lobbying by influential people, including Professor John Mulvaney who was a member of the Pigott inquiry, the first Australian course in Materials Conservation was established at the CCAE at the end of 1977 with a commencement date of March 1978. Colin was appointed to run the program and so began his career as an educator.

He arrived in December and working like a madman, recruited students and staff, designed the courses, set up the labs and appeared bright-eyed and bushy tailed to deliver the first lectures to the new students, most of whom didn’t really know what conservation was all about. I was one of those inaugural students and I can attest that Colin’s dynamism and passion for conservation won us over in those first few weeks. We were real guinea pigs and he drove us mercilessly. We perhaps did not appreciate the strain that he was under – he was dealing with a group of students ranging from some just out of high school to some who were artists, others were scientists or engineers, some representing sundry other walks of life and a few who had real experience in conservation. In addition he had to prove that the course was going to be successful.

Colin successfully operated that program for 24 years. In that time he recruited an interesting group of staff – some more successful than others and a fascinating array of students. The students came with a broad range of backgrounds and skills – some just out of high school, some were artists, others were scientists or engineers, a few had real experience in conservation and/or museums and others came from sundry other walks of life. Over this time and through many changes Colin managed to endear himself to generations of conservators inspiring them to become true professionals. He was a genuine scientist-encouraging research, embracing debate and fostering diversity. He never shied away from a good argument. However he was also always ready to party, to act the clown and to have fun.

During his years of tenure he had to accommodate massive changes: budget cuts; a change from the CCAE to the University of Canberra (UC); a range of vice-chancellors and demands from the conservation profession. He established the Cultural Heritage Management program to put conservation into a wider context and broadened the scope of the program to include Indigenous students and the wider community collections. In its 25 years of operation the program offered courses ranging from Associate Diploma, Bachelor, Master to PhD levels. It graduated 338 students, the majority still working in conservation – most nationally but some internationally, where Canberra graduates are always welcome, being recognised as well trained and competent. The profession has grown to a stage where there are now more than 600 working in the field in Australia.

During his years of tenure he had to accommodate massive changes: budget cuts; a change from the CCAE to the University of Canberra (UC); a range of vice-chancellors and demands from the conservation profession. He established the Cultural Heritage Management program to put conservation into a wider context and broadened the scope of the program to include Indigenous students and the wider community collections. In its 25 years of operation the program offered courses ranging from Associate Diploma, Bachelor, Master to PhD levels. It graduated 338 students, the majority still working in conservation – most nationally but some internationally, where Canberra graduates are always welcome, being recognised as well trained and competent. The profession has grown to a stage where there are now more than 600 working in the field in Australia.

Over the years Colin continued to conduct and supervise research and to publish, focusing on a variety of scientific themes, particularly iron corrosion but also rock art and paper as well as training. His magnum opus is Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects, published by Butterworth-Heinemann in the Conservation and Museology Series in 1988. He has a total of over 120 publications.

Over the years Colin continued to conduct and supervise research and to publish, focusing on a variety of scientific themes, particularly iron corrosion but also rock art and paper as well as training. His magnum opus is Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects, published by Butterworth-Heinemann in the Conservation and Museology Series in 1988. He has a total of over 120 publications.

In 1994, Colin was made Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for services to conservation of historical artefacts, and during the same year he was appointed Special Professor of Cultural Heritage Conservation at the University of Canberra. In the following year he was appointed Fellow of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering (FTSE).

In the mid-1970s, with the support of the WA museum, Colin began attending international conferences delivering papers on his research into the treatment of underwater archaeological materials. The scope of his knowledge and experience soon resulted in his appointment to the first of many positions in international organisations. In 1978, the first year of the CCAE program, he was made Coordinator of the Working Group on Waterlogged Wood of the International Council of Museums-Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC). Over the next 26 years he served on two other Working Groups-Training (1981-1990) and Preventive Conservation (2002 -2004). He also served as a member of the Directory Board (1981-1984). His position on the board was a contributing factor for Australia being awarded the responsibility for hosting two of the Triennial ICOM-CC conferences-the first in 1987 in Sydney and the second in 2014 in Melbourne. Colin was national coordinator of the 1987 meeting and at the latter was awarded the ICOM-CC medal in recognition of his vital role both within the organisation itself and in the field of conservation at large.

Another major international organisation that benefitted from Colin’s expertise was ICCROM, the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property based in Rome. In the early 1980s, Colin contacted ICCROM with a proposal to develop preventive conservation programmes in the Pacific basin. This resulted in a joint needs assessment carried out by ICCROM and the University of Canberra from 1991 to 1993. An eventual outcome was the formation of the Pacific Islands Museums Association (PIMA) to coordinate training and networking in this region.

In 1984 Colin was elected to the ICCROM Council, where he served in an active capacity until 1995. He was member of the Standards and Training Committee from 1986, and served as Vice Chair of the committee until 1990. From 1990 to 1994, he was Chair of the reformed Academic Advisory Board. In this position, he contributed significantly to the development of ICCROM’s training strategies and programme development. In this capacity, he contributed to revising the Training Guidelines then adopted by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) General Assembly in 1993. He was also Chair of the Ad Hoc Committee to revise Statutes, Procedures of Council, General Assembly and Staff Regulations in 1990-1993, an activity which resulted in major revisions in ICCROM’s administration. As such, Colin was a key actor in a critical period of ICCROM’s programme development from the 1980s to the 1990s.

For these many important national, regional and international contributions, he was honoured with the ICCROM Award in 2003. At that time he was praised as “clearly among the most versatile and capable conservators of his generation…..His informal manner, his ability to motivate and inspire, have made him a mentor and colleague to so many of those practicing conservation today.”

In 2014 he received the International Council of Museums Committee-Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) medal in recognition of his influential role within the field of conservation. He served on the councils of three major international organisations: ICCROM, The International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (IIC) and ICOM. In May 2016 he was posthumously awarded Honorary Fellowship of IIC, thereby recognising him as one of the greats of the conservation profession internationally.

The list of Colin’s achievements is long but many have said that his true legacy is the passion for conservation that he created in the hearts of generations of conservators. It is they who will take the profession forward. He provided the support, mentorship and inspiration that has motivated many. His passion, drive, kindness, sense of fun, quirky sense of humour and sheer joy of life are widely recognised. His kindness and understanding of human nature meant that he was prepared to take risks with people and to assist in keeping them on track when they faltered. Significantly, he treated his students as people first and students second. Out of class he was always ready to party, to act the clown and to have fun. He changed the lives of many people.

It is tempting to say that the stars were aligned in the late 1970s for the birth of the Australian conservation profession and for Colin to be the prime mover. He was ideally positioned to educate and mentor an ever-growing number of students and to be the voice of conservation in Australia. While Bill Boustead-the first person in Australia to be appointed as “conservator” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1954 and the initiator of a conservation training cadetship in the 1960s-can lay claims to be the Father of Australian Conservation profession, it is Colin, with the broad scope of his influence, who has rightly earned that title. Perhaps Boustead should be known as the Grandfather of the profession.

It is tempting to say that the stars were aligned in the late 1970s for the birth of the Australian conservation profession and for Colin to be the prime mover. He was ideally positioned to educate and mentor an ever-growing number of students and to be the voice of conservation in Australia. While Bill Boustead-the first person in Australia to be appointed as “conservator” at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1954 and the initiator of a conservation training cadetship in the 1960s-can lay claims to be the Father of Australian Conservation profession, it is Colin, with the broad scope of his influence, who has rightly earned that title. Perhaps Boustead should be known as the Grandfather of the profession.

Colin fought to keep the UC program viable but factors outside of his control or influence resulted in its closure in 2002. He resigned in 2002 and was appointed Emeritus Professor (2002-2004). In his 35 years working in the conservation profession Colin witnessed many changes.

On Colin’s retirement in 2002 the AICCM and the profession held a celebratory event at the National Museum of Australia. The address Colin gave and Jan Lyall’s response can be read in the AICCM Newsletter No 85 of December 2002. Which can be found here: https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/NationalNewsletter_85_Dec2002_0.pdf

In 2003 Colin was interviewed by Dr Jan Lyall on the history of the Conservation Profession in Australia. This is now part of the NLA oral history collection and can be found online at: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-213705945

In the interview Colin said that he was proud to be have been instrumental in shaping the profession, that he had no regrets and that he was confident that the profession would survive, albeit in a different way. He acknowledged the support and mentorship of people such as David Ride, John Mulvaney and Gough Whitlam. He said that he saw his career as a mixture of chance and ambition and that he had stayed in it by choice though he had opportunities to move into management positions in museums and into academia.

In his retirement Colin spent the last 14 years of his life living happily with his wife Gwyn on the NSW South Coast. He displayed the same level of passion and enthusiasm for his interests in retirement that he did in his conservation life. He became very involved with the local golf club, made regular contributions to the Men’s Shed, sang in the local choir, was passionate about his orchids, and continued drinking good wine and enjoying good food. He and Gwyn enjoyed quite a lot of international travel and in the last year he took up sculpture. The project that he undertook with a friend from the Men’s Shed was an almost life size sculpture in Hebel Stone of St Sebastian, the patron saint of 20 January, Colin’s birthday. I think that in Colin’s last month of life when he was in so much pain he must have felt empathy for his patron saint.

In his retirement Colin spent the last 14 years of his life living happily with his wife Gwyn on the NSW South Coast. He displayed the same level of passion and enthusiasm for his interests in retirement that he did in his conservation life. He became very involved with the local golf club, made regular contributions to the Men’s Shed, sang in the local choir, was passionate about his orchids, and continued drinking good wine and enjoying good food. He and Gwyn enjoyed quite a lot of international travel and in the last year he took up sculpture. The project that he undertook with a friend from the Men’s Shed was an almost life size sculpture in Hebel Stone of St Sebastian, the patron saint of 20 January, Colin’s birthday. I think that in Colin’s last month of life when he was in so much pain he must have felt empathy for his patron saint.

Colin’s local standing in the Tuross community is made clear by the fact that his obituary appeared in the local paper, the Tuross Giant of May 2016.

Colin Pearson passed away on 17 April 2016 at Moruya Hospital after a short illness. He is survived by his wife Gwyn and his children John, Victoria and Richard.