My name is Rynno Gabriel Luis Torres Garde; Gab, for short. I am a first-year student in the Master of Cultural Materials Conservation Program at the University of Melbourne. I am currently working at Museum of Brisbane, and have worked and volunteered with six cultural institutions across the Brisbane area in various collections and curatorial roles. This overly detailed, cathartic, stream-of-consciousness article unpacks my personal exploration of my cultural and national identity, and the role that the Master’s Program and the field of conservation have played in my journey.

I was born and raised in Metropolitan Manila, in the Philippines. Like many Filipinos, especially those in the Metropolitan Manila area, I grew up consuming mostly Western media, and was not particularly enthused by my local culture. In the Philippines, proficiency in written and spoken English is often erroneously associated with intelligence and high social standing. This is a legacy left behind by the Americans, whose decades-long colonisation of the islands they termed a ‘benevolent assimilation’. The Philippines is still recovering from hundreds of years of colonisation courtesy of Spain and the United States, the unfortunate by-product of which is a not-uncommon attitude of self-loathing, and a love for all things Western, born out of rhetoric originally used to keep colonised Filipinos from resisting oppression.

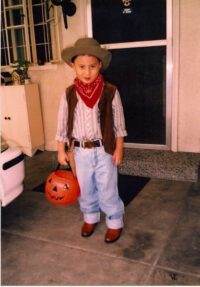

I came to Australia six years ago, and have since become an Australian myself. Coming from the overpopulation and corruption of a developing nation, Australia was a clean, laid-back paradise, filled with opportunity. Upon first arrival to my new home, I immediately felt pressure to assimilate to the prevalent culture. I received well-intentioned advice and coaching from my father, who had already been living here for ten years, with the hope of making me ‘more Australian’, in order to avoid being the target of prejudice and racism. He acknowledged the presence of racial prejudice in Australia, but never spoke of his own experiences. Despite my outwardly Filipino features, I nevertheless made a conscious effort to mask my otherness, by changing the way I dressed, bleaching my jet-black hair to a medium brown, and even adopting a more American-influenced accent. On my father’s suggestion, I even relinquished the original pronunciation of my name; ‘Gabriel’ was now pronounced with a long ‘a’. By altering my name, the way I spoke, and the way I looked, it was hoped that I could better take advantage of what Australia had to offer me. Of course, I received occasional racial verbal abuse regardless, and also lost touch with my cultural identity in the process.

In 2019, I went from an undergraduate degree in psychology to postgraduate studies in museum studies, filled with regret that I had not done my undergraduate studies in archaeology or visual arts instead. Museum studies opened my mind to the issues surrounding cultural heritage. I was particularly fixated on the ever-contentious issue of repatriation, and wrote a passionate essay calling for the repatriation of the British Museum’s scores of dubiously acquired objects. At around this time, I joined the Visitor Experience Team at Museum of Brisbane, and was put on a secondment as a collections assistant during the Museum’s forced closure as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While working on a partial audit of the collection, I discovered a love for working with objects, whether it be through conducting condition reports, cleaning, labelling, or re-housing. I was then given an opportunity to complete a short contract as an assistant conservator, doing supervised remedial stabilisation work, mount construction, and preliminary condition reporting for the Pattern and Print: Easton Pearson Archive national touring exhibition. On another occasion, I was also given the exhilarating task of stitching a scarf onto a mounting board with monofilament. Pleased with my work, and seeing my passion and my eagerness to gain new skills, the Collections team at the museum encouraged me to pursue a career in conservation. They gifted me with hake brushes, a bone folder, a scalpel, and forceps to help me start my kit. ‘Go on and be a conservator, Gab.’

In 2019, I went from an undergraduate degree in psychology to postgraduate studies in museum studies, filled with regret that I had not done my undergraduate studies in archaeology or visual arts instead. Museum studies opened my mind to the issues surrounding cultural heritage. I was particularly fixated on the ever-contentious issue of repatriation, and wrote a passionate essay calling for the repatriation of the British Museum’s scores of dubiously acquired objects. At around this time, I joined the Visitor Experience Team at Museum of Brisbane, and was put on a secondment as a collections assistant during the Museum’s forced closure as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. While working on a partial audit of the collection, I discovered a love for working with objects, whether it be through conducting condition reports, cleaning, labelling, or re-housing. I was then given an opportunity to complete a short contract as an assistant conservator, doing supervised remedial stabilisation work, mount construction, and preliminary condition reporting for the Pattern and Print: Easton Pearson Archive national touring exhibition. On another occasion, I was also given the exhilarating task of stitching a scarf onto a mounting board with monofilament. Pleased with my work, and seeing my passion and my eagerness to gain new skills, the Collections team at the museum encouraged me to pursue a career in conservation. They gifted me with hake brushes, a bone folder, a scalpel, and forceps to help me start my kit. ‘Go on and be a conservator, Gab.’

In 2020, I began the application process for the Master of Cultural Materials Conservation Program at the University of Melbourne. I conducted extensive research into the program, by first researching my potential lecturers, and tracking their career paths through LinkedIn. Upon looking at their research areas of interest, I noticed a focus on the Asia-Pacific region, and I was shocked at the number of references to the Philippines in their research. I delved deeper into their activities and discovered a great diversity in their involvement with my homeland. The researchers at the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation have conducted research in Bohol, Ilocos, and Manila, and foster strong, positive relationships with researchers, leaders, and communities in the Philippines and across the Asia-Pacific. I had always felt that Filipinos were mostly ‘invisible’ in Australia and the rest of the Western world, and any mention of the Philippines in popular culture provides an inexplicable, dopamine-fuelled feeling of validation. There was a time when I used to mock other Filipinos for what I perceived was a shallow sense of pride. However, after six years of feeling invisible, feeling constantly othered, and being on the receiving end of both overt and systemic racial discrimination, I learned to take some pride in my identity.

Once the lectures commenced, it took an extraordinary amount of self-restraint to not ask every single question I had about my lecturers’ involvement in the Philippines. There was great emphasis placed on cultural sensitivity, cultural collaboration, and deferring to the expertise of cultural leaders and community members. I was able to draw on my knowledge of the psychological principles of collaboration and group processes to aid my understanding of these conservation issues; perhaps my undergraduate degree was not completed in vain. However, I feared that, as the Filipino of the class, I would be called upon as an expert in Philippine cultures. In reality, these lecturers had spent more time in these communities than I ever had. While I had the cultural background and could read the Filipino psyche, they had the experience, and had engaged so deeply with these communities. Inevitably, the discussions led me to ponder the state of cultural materials in my homeland. This was the first time, in a long time, that I had engaged in critical thought regarding my own heritage. I wondered how many Philippine ethnographic objects were currently in the hands of our former colonisers: Spain and the United States. I mused that Metropolitan Manila now has very little connection to its pre-colonial past, with most traces of pre-colonial cultural materials and practices having been erased by the Spanish, who used Manila as their base of operations and employed cultural erasure (under the guise of evangelism) as a key tool for colonisation. Many other regions in the Philippines, however, were fortunate enough to keep older cultural practices alive, especially those in more remote areas. I also remembered my own apathy towards the rich living cultures that still thrive in the Philippines; an apathy that was shared with many others I knew. This train of thought led to frustration, and the desire to act. I began to feel a strong sense of protectionism for a national identity that I had shunned for so long.

In this article, I use the terms ‘cultural identity’ and ‘cultural heritage’ several times, but what do these actually mean in this case? ‘The Philippines’, named after Spanish Monarch Philip II, is an artificially grouped nation; in reality, the islands consist of hundreds of discrete cultural groups. The confusion involved with using the term ‘indigenous’ in the Philippines constitutes another topic of its own. My early studies in conservation have now primed me to challenge my preconceptions of cultural homogeneity, especially in my homeland. My father is from Laguna, predominantly populated by the Tagalog ethnic group, and my mother is from Pampanga, home to the Kapampangan ethnic group. Having grown up in Metropolitan Manila, I was raised in a Tagalog society, speaking ‘Filipino’, a post-colonial variant of the Tagalog language. I also have a percentage of Chinese ethnic heritage, but have never identified with Chinese culture. What, then, is my cultural identity? There have been pre-colonial archaeological findings in Manila, but the ‘original’ cultures simply could not endure the destructive cultural erasure of colonialism. There have also been pre-colonial written texts found in Laguna, but the writing system is not currently in use. My Hispanised name is evidence of this erasure and loss of pre-colonial identity that so many cultures across the globe were subjected to. Post-colonial societies have had relatively little time to heal, and adapt to their circumstances. The Philippines has only been independent since the end of the Second World War, and is marred by the colonial legacies of corruption, feudalism, classism, and colourism.

In this article, I use the terms ‘cultural identity’ and ‘cultural heritage’ several times, but what do these actually mean in this case? ‘The Philippines’, named after Spanish Monarch Philip II, is an artificially grouped nation; in reality, the islands consist of hundreds of discrete cultural groups. The confusion involved with using the term ‘indigenous’ in the Philippines constitutes another topic of its own. My early studies in conservation have now primed me to challenge my preconceptions of cultural homogeneity, especially in my homeland. My father is from Laguna, predominantly populated by the Tagalog ethnic group, and my mother is from Pampanga, home to the Kapampangan ethnic group. Having grown up in Metropolitan Manila, I was raised in a Tagalog society, speaking ‘Filipino’, a post-colonial variant of the Tagalog language. I also have a percentage of Chinese ethnic heritage, but have never identified with Chinese culture. What, then, is my cultural identity? There have been pre-colonial archaeological findings in Manila, but the ‘original’ cultures simply could not endure the destructive cultural erasure of colonialism. There have also been pre-colonial written texts found in Laguna, but the writing system is not currently in use. My Hispanised name is evidence of this erasure and loss of pre-colonial identity that so many cultures across the globe were subjected to. Post-colonial societies have had relatively little time to heal, and adapt to their circumstances. The Philippines has only been independent since the end of the Second World War, and is marred by the colonial legacies of corruption, feudalism, classism, and colourism.

Since I began writing this article, I have gone through the introductory treatment course, which felt like surreal wish fulfilment as I learned colour matching, metals cleaning, paper examination, wood examination, and basket repair (see image for my imperfect first attempt at re-creating, colour matching, and re-weaving four missing segments with Japanese tissue). While preserving objects is an important aspect of conservation, and is what drew me to the profession, I am beginning to learn that conservation involves much more. Understanding cultural context is essential for understanding the object. Objects have a powerful link to a culture’s practices and societal expectations, and are a tangible representation of that culture’s identity. What significance, then, does an object hold if it has lost its connection to its culture of origin, and can no longer be identified? Moreover, what significance does an object hold when its culture of origin no longer recognises its importance? The second question perturbs me deeply, as I contemplate my homeland’s poor public education system. The cultural institutions in the Philippines have taken great measures to attempt to piece together the fragments of our lost pre-colonial cultures, but it is also important to remember that cultural heritage does not only exist in the past. This is especially true for fragmented, post-colonial nations. Cultures are not static; they evolve and change with time. Before the arrival of the Spanish, there were Arab-influenced Muslim Sultanates and Indian-influenced Rajahnates in the Philippines. The Philippine languages have influences of Sanskrit, Arabic, Malay, Hindi, Chinese, Spanish, and English; these influences were absorbed at various points in history, and some before recorded history. Perhaps there is not a single iteration of a culture that is more authentic than another. ‘Authenticity’ in conservation, after all, is highly subjective. My Hispanised name is a part of my heritage, as is the Barong Tagalog, which was introduced during the Spanish colonial period. However, it is still vital to research and ascertain ‘pre-colonial’ cultural heritage (a culture’s state in a specified period of time), in order to obtain the full historical context necessary to understand a culture.

I am proud to be Filipino-Australian, and I will be even prouder to call myself a Filipino-Australian conservator, when the time comes. Being Filipino means taking on the colonial baggage that comes with our rich, layered history, and the field of conservation has provided me with a new lens through which to view my own identity. I am grateful to be involved in a field that treats cultures and communities with such respect, and provides an enormous amount of support for its new students and emerging professionals. I am also grateful that the research the Grimwade Centre has conducted allows cultural heritage concerns in the Asia-Pacific to be discussed in places like Australia. It is only fitting that Australian researchers and institutions turn their focus towards their closest neighbours. I look forward to seeing how my sense of national and cultural identity will continue to evolve, as my understanding of the changing nature of identity grows while progressing through the program. I am hoping to meet and exchange ideas with as many of you as I can, dear AICCM members, cultural heritage professionals, and conservation enthusiasts, as I navigate this exciting new world.

I am proud to be Filipino-Australian, and I will be even prouder to call myself a Filipino-Australian conservator, when the time comes. Being Filipino means taking on the colonial baggage that comes with our rich, layered history, and the field of conservation has provided me with a new lens through which to view my own identity. I am grateful to be involved in a field that treats cultures and communities with such respect, and provides an enormous amount of support for its new students and emerging professionals. I am also grateful that the research the Grimwade Centre has conducted allows cultural heritage concerns in the Asia-Pacific to be discussed in places like Australia. It is only fitting that Australian researchers and institutions turn their focus towards their closest neighbours. I look forward to seeing how my sense of national and cultural identity will continue to evolve, as my understanding of the changing nature of identity grows while progressing through the program. I am hoping to meet and exchange ideas with as many of you as I can, dear AICCM members, cultural heritage professionals, and conservation enthusiasts, as I navigate this exciting new world.