In 2021, the Ligatus Summer School program was held, offering two courses over two weeks, and one of which, European Bookbinding 1450–1830, tutored by Professor Nicholas Pickwoad, I was fortunate to attend. The course is supported by the Ligatus Research Centre, University of the Arts London, and the Saint Catherine Foundation.

Sixteen participants tuned in from all over the world—book and paper conservators from Europe, the UK, the USA and Singapore—to share in Prof. Pickwoad’s vast knowledge of the history of the book.

Prof. Pickwoad is the director of Ligatus, has a doctorate in English literature and trained in both bookbinding and book conservation with Roger Powell. Over the years, he has taught book conservation for numerous universities and held many classes via Ligatus. Prof. Pickwoad has an interest and wealth of knowledge in European bookbinding, particularly the era of the hand printing press and trade bindings, all of which he conveyed over a comprehensive five-day course.

Ten sessions were presented over the five days, with lectures during the mornings followed by an afternoon session each day, where Prof. Pickwoad selected binding examples from his personal collection. For me, in the southern hemisphere, this meant late evening starts and early morning finishes.

On the first day, students learned how to date bindings, briefly touching on finishing tools, discussed aggregate dating, and reviewed medieval binding styles. Emphasis was placed on the need for students to understand not only bookbinding as a craft, but also the book trade, book culture, the binder at work, and how all these factors developed over time. In reference to medieval books, Prof. Pickwoad drew on examples from medieval paintings. Using the medieval triptych Annunciation, 1443–4, by Barthélemy d’Eyck as a teaching tool, Prof. Pickwoad pointed to a collection of books of various value: a girdle book; a silk covered book with gauffered edges; a plain library binding; a pink alum-tawed stationery binding with tackets; and a small-format limp parchment binding. The next session followed an exploration of binderies showing historical illustrations, following books in sheets through to their binding. Prof. Pickwoad drew on various illustrations from Dirk de Bray’s 17th century technical account A Short Instruction in the Binding of Books. We finished day one looking at Prof. Pickwoad’s personal collection. He showed an example of printed octavo in sections, surviving the centuries unbound, and an almost intact printed duodecimal sheet (12 pages per side) that likely survived all these years as waste. Prof. Pickwoad revealed inscribed instructions to and from binders and owners within books, and showed examples of finishing, tooling and decorative endpapers that may indicate time, place or ownership, as a way of loosely dating bindings.

Aix Annunciation (1443–1445) – Barthélemy d’Eyck

Day two’s focus was on stitched books, sewing techniques and a variety of sewing supports. Prof. Pickwoad shared many illustrations he has drafted to convey a diverse range of sewing structures, which he has documented over the years. He paired these illustrations with examples of books demonstrating what one can and can’t see, due to the condition of the book. We were shown the development of raised supports and thongs through to recessed supports, deceptive practices and hollowback spines. Prof. Pickwoad showed examples of edge treatment and various spine lining methods that may be indicative of binding location. In the afternoon he drew from his own collection, showing many books that are simply stitched and never intended to be sewn to boards or covered.

Day three required our undivided attention as we navigated the vast terrain of books before boards. Prof. Pickwoad showed us many examples of temporary bindings that were sewn but not covered, used, and read this way. He shared an example of Francois Boucher’s portrait of Madame de Pompadour, 1756, surrounded by her ‘uncovered’ books, symbolising a well-read lady of the French court, eager to read her books before they are covered. We dived deep into the variations of stitched books, link-stitch and long-stitch, wrapper covered books, lace attached bindings and tacketed bindings. And then further into the intricacies of laced bindings with paper and parchment covers, laced bindings with boards and, lastly, case bindings. We were shown some good examples of soft materials used as substitutes for boards such as cartonnage covers, printed and marbled paper wrappers, German painted parchment, green parchment from England and translucent parchment showcasing paintings on soft supports underneath. From his own collection, Prof. Pickwoad showed students examples of stitching and sewing in books. We assessed the quality and style of sewing to gain a sense of whether the book was temporarily sewn or intended to be covered with sewing intact, and assessed sewing or stitching style and quality, which may indicate value of the text, if it was made inexpensively and quickly. Similarly, we looked at materials used for wrappers, whether they be decorative marble or paste papers compared to printed waste.

Madame de Pompadour (1756) – Francois Boucher

On day four we moved on to books with boards, exploring a variety of materials such as wood, scaleboard, laminated and paper boards. Prof. Pickwoad explained how boards would protect and keep the textblock flat, especially parchment textblocks, with the addition of clasps to effectively act like a small press. Eventually binders moved on to lighter weight and cheaper alternatives to wooden boards and we saw many examples of these materials. Prof. Pickwoad discussed the many variations of board attachments, which directed us towards endbands, beginning with worked-on endbands through the development of stuck-on endbands. For example, we began with Greek bindings, viewed plain endbands with no bead, then more decorative coloured and patterned bands. We looked at examples made with different core materials such as leather, cord, cane, wooden dowel and rolled papers. Prof. Pickwoad showed examples of early stuck-on endbands, as early as the 16th century, and more examples through to the early 19th century. After the morning lectures he sifted through examples of his own books, showing one particularly strange-looking German binding, with a block that was thicker in depth than the width of its boards, commenting on its ‘unwieldy’ handling.

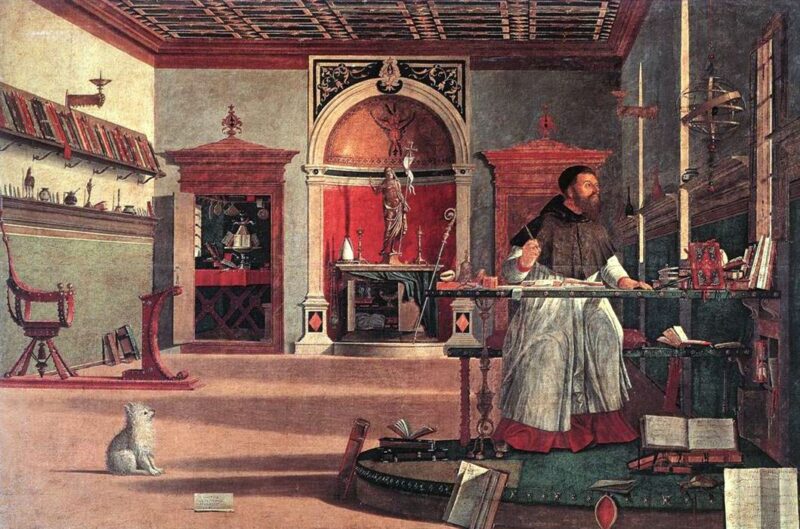

Our last day covered coverings! We learned about uncovered bindings in boards, covering materials, covering techniques, and half and quarter bindings. Prof. Pickwoad showed us many examples of books that had survived uncovered, examples where owners decided not to cover their books or books never intended to be covered. We looked at silk-covered books, embroidered books, jewel-covered books (treasure bindings) and different leathers such as goat, hairsheep and sheep. We viewed decorative leather techniques such as onlays and inlays, embossed leathers, reversed leathers (flesh side) and alum-tawed skins. In his final lecture we explored the economy of bindings, looking at inventive examples of binders using waste, board reuse and examples of parchment repairs. We then explored books for specific uses, such as account-books, schoolbooks, and portable books. We finished on the topic of storage and how it developed over time. Prof. Pickwoad referenced the tilting shelves depicted in Vittore Carpaccio’s St Augustine in His Study, 1502, the flat stacked books titled on their head in Guercino’s Portrait of Francesco Righetti, 1628, before books were eventually shelved with their spines facing out, labels and raised bands visible, much like we store our books today. Our final virtual tour through Prof. Pickwoad’s personal library presented us with a mixture of bindings showing titles inked on their heads, and leather- and canvas-covered schoolbooks in standardised format. We saw one very economic binding utilising a large leather waste piece for covering and waste print predating the text by 200 years. We looked at various covers with exotic embroidery and velvet, lace-stencil frames on leather, reverse calf bindings and a particularly stunning marbled and painted leather binding, evocative of a Jackson Pollock painting.

St. Augustine in His Study – Vittore Carpaccio (1502)

Participating in the course was extremely eye-opening to the varied and vast collections of books from this period, and the challenges conservators face in assessing and caring for these materials. I highly recommend this course to anyone working closely with book material, especially conservators within libraries. Prof. Pickwoad is an advocate for looking at books closely, assessing structures with an awareness of the order in which they were likely made, not assuming but describing what one sees, and refining our terminology as we wade through this complex field. He encourages his students not to be daunted by this tremendous task, and instead to keep in mind one of his favourite and somewhat comforting quotes: ‘We must have some challenging assertions before we notice how wrong they are’ — Graham Pollard, ‘Changes in the Style of Bookbinding, 1550–1830’, The Library, s5-XI, Issue 2, June 1965, pp. 71–94.