As in-person training opportunities for bookbinding in Australia are rare, it was an immensely valuable experience to travel to Sydney in June 2023 to attend three workshops with two internationally renowned bookbinders: ‘Limp Vellum Binding’ and ‘Library-Style Binding’ with Michael Burke at the NSW Guild of Craft Bookbinders in Rozelle, and ‘Full (Simplified) Leather Binding’ with Dominic Riley at Andersen’s Bindery in Redfern. After nine days, I returned to Melbourne with three useful reference models, extensive notes, and a head full of ideas that I have endeavoured to summarise below.

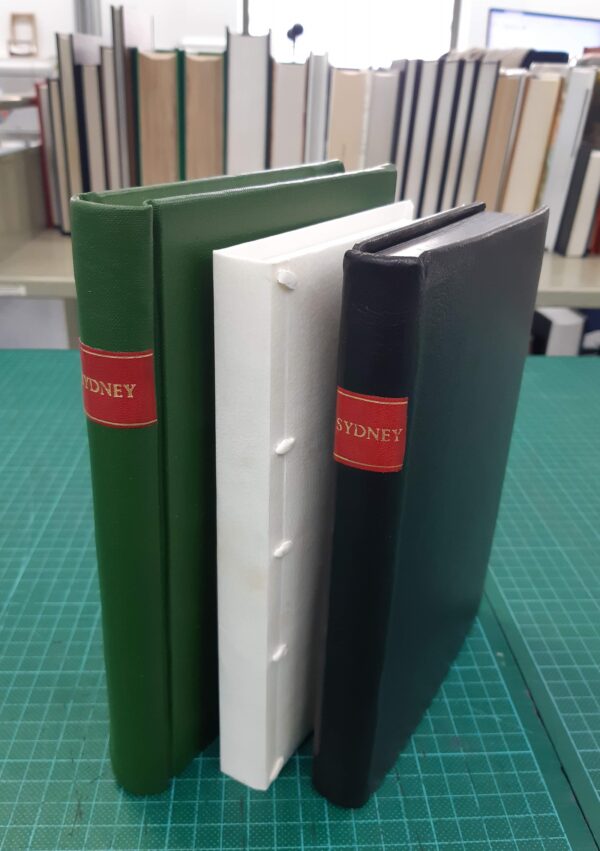

(Left to right) Completed book models: library-style, limp vellum and full (simplified) leather.

Limp Vellum Binding

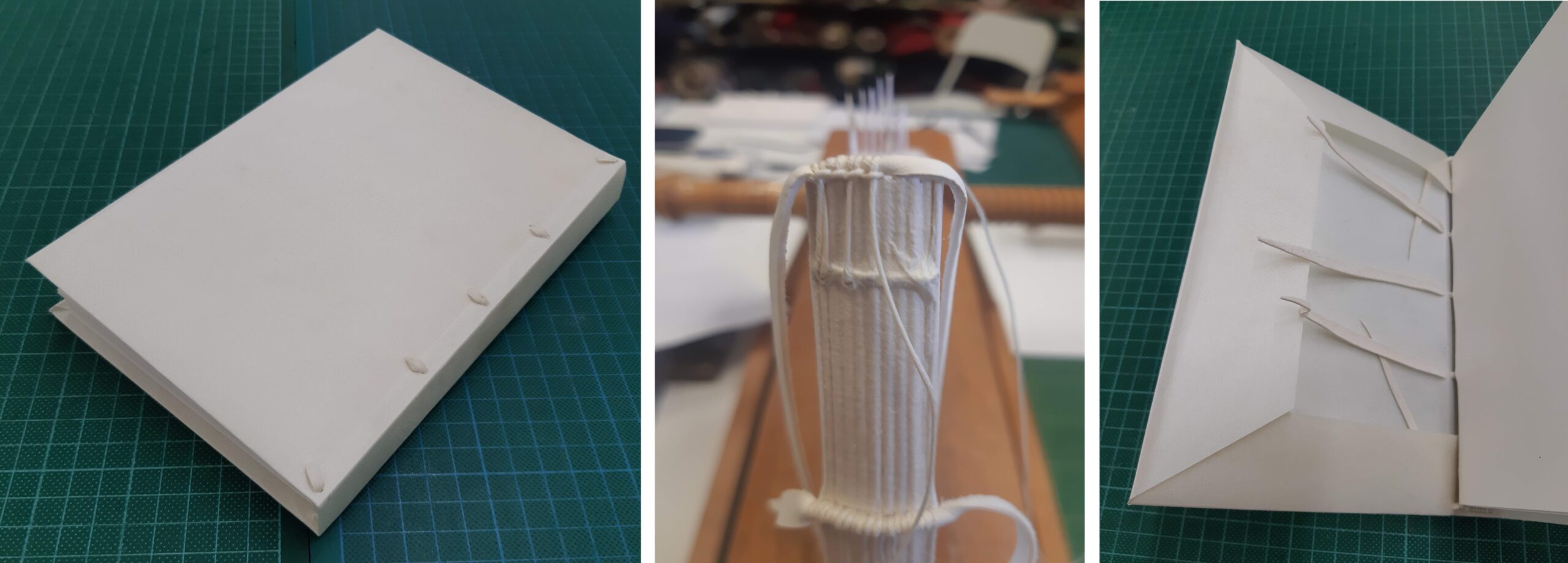

My training began with the construction of a model limp vellum binding – an elegant structure, with a notable resilience that was observed in the aftermath of the 1966 Florence floods and thorough studies of the structure by Christopher Clarkson. The model features packed sewing and headbands sewn on alum-tawed sheepskin supports, laced through a vellum cover.

In addition to the flexible structure, the exceptional quality of these materials is integral to the bindings’ longevity. Also critical was understanding how alum-tawed skins and vellum are produced, and the effect of these processes on material characteristics, such as sensitivity to moisture. As a non-adhesive binding, the study of this historic technique may also inform the construction of minimal intervention conservation bindings.

(Left to right) Limp vellum binding; headband sewing in progress; laced into vellum cover.

Library-Style Binding

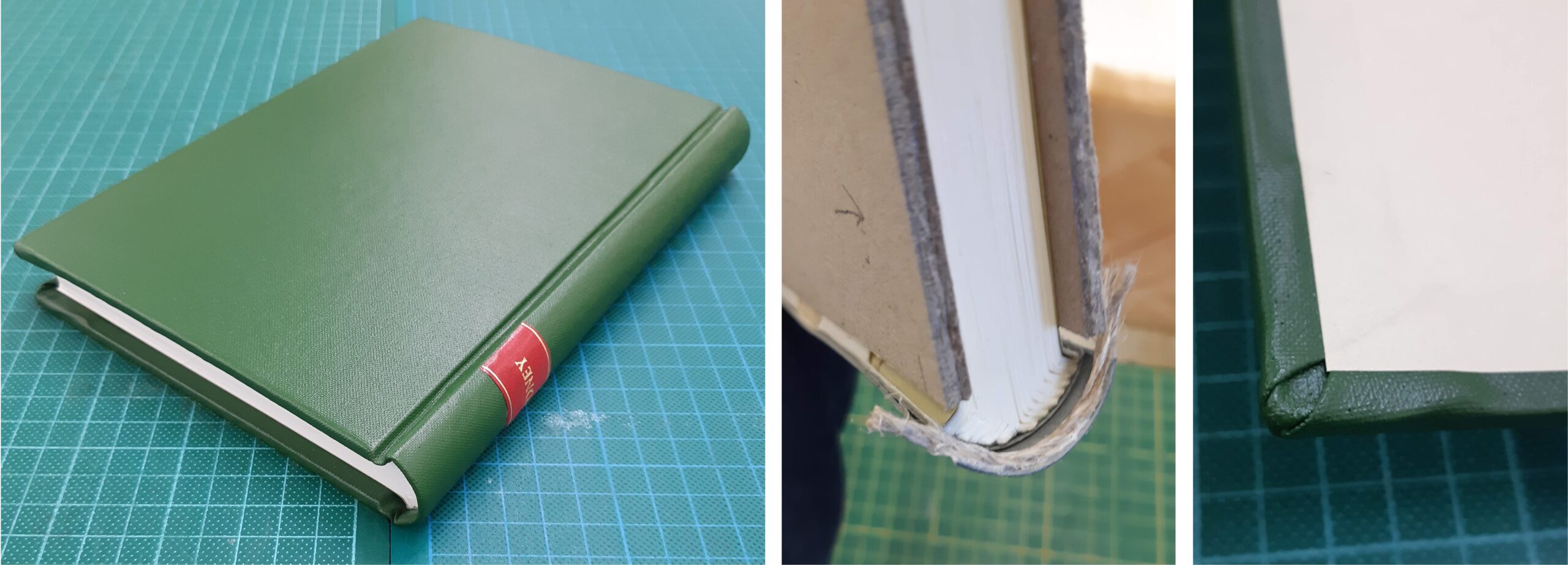

The next model produced, the library-style binding, was less elegant, but tremendously strong. Influenced by medieval account book structures, it was developed in the late 19th century as an economical means of binding library books needing to endure heavy use by patrons. Features included endpapers reinforced with cloth, linen tapes, a substantial joint (‘French groove’), flanges inserted into split-boards, a kraft paper hollow, a heavy buckram cover with hemp cord to form headcaps and rounded (untrimmed) corners.

Such a heavily reinforced binding may be less necessary today with changing patron usage. Nevertheless, it was useful to recognise the construction and function of each structural element. These techniques could be applied selectively to smaller books requiring repair, or to very large, heavy books requiring reinforcement.

(Left to right) Library-style binding; hemp cord adhered to hollow to form a headcap; untrimmed, rounded corners.

Full (Simplified) Leather Binding

The third model was constructed over five days, allowing ample time to practise new skills and reinforce more familiar techniques. The model was ‘simplified’, in the sense that the leather case was made off the book. But it remains an historically relevant technique, used by trade binders such as Shepherds in London. It featured marbled endpapers strengthened with a cloth joint, unsupported sewing in the herringbone style, graphite edge decoration, leather headbands, shaped millboard covers, and spine linings of mull, paper, and rabbit-skin glue.

Developing skills in paring leather, as well as comprehending the functional properties of bookbinding adhesives—hot animal glue, starch paste and EVA—was hugely valuable in better understanding deterioration pathways, as well as building confidence in book conservation treatments.

(Left to right) Full (simplified) leather binding; applying rabbit-skin glue to book spine; leather headband and graphite edge decoration.

After so much self-directed and online study of the last few years, it was a delight to attend in-person and learn hands-on, face-to-face, in a collaborative setting. Class sizes were limited to 6–8 participants, allowing enough room to move and equipment to share. While the experience of participants varied—from those who had never made a book before, to seasoned Guild members—it was a testament to the skill of the teachers (and their assistants!) that no one was left behind.

Dominic and Michael both share a lively and very engaging style of delivery. A key aspect of their teaching is that no knowledge is assumed. While they take their students ‘back to basics’, it is far from tedious. Rather, it’s a thorough and fascinating means of learning that helps to build even greater appreciation for the craft of bookbinding, of how book structures have evolved and been refined over hundreds of years as functional objects. Their approach encourages curiosity, working to inform the novice bookbinder and unpacking any assumptions a more seasoned practitioner may hold.

They both imparted a respect for good quality materials (vellum, alum-tawed skins, and leathers), conveying their in-depth knowledge of manufacturing processes, based on longstanding relationships with suppliers (Cowley’s, Hewitts and Harmatan). They also stressed how these materials should be handled with great care, such as always using a fresh scalpel blade, starting with a paper template, practising on scraps, and working on a clean surface – crucial principles to always remember and follow, no matter your level of experience.

The three book models emphasised the continuity of the bookbinding tradition over time, and the emergence and functionality of different structural features. Undertaking back-to-back workshops was a great opportunity to hone hand skills and improve my understanding of how certain binding structures might be re-engineered or applied through conservation treatments.