From February to March of 2017, six pith paper paintings were treated at the University of Melbourne’s Grimwade Centre for Cultural Conservation. The project was undertaken by two student conservators working simultaneously in close collaboration; Empress, His Lady and Inferior Mandarin were treated by Rebecca Barnott-Clement and Emperor, Manchu Tartar General and His Lady were treated by Cancy Chu The challenge of treating an unusual material and investigating multi-layered objects proved to be an especially rewarding learning experience.

STEP 1: EXAMINING THE PAINTINGS

From an initial examination, the primary support of the framed miniature paintings appeared to be a thin, paper-like material. The small, cream sheets were extremely lightweight, fragile, prone to scratching and slightly translucent. Areas with media contact had swollen to produce an embossed, three-dimensional effect, with high colour density. Research showed that this swelling property was consistent with the response of pith paper when painted, as the pigment welled in the cup-like pith cells and reduced the materials’ ability to shrink back on drying (Boone 2003). Further research was needed to understand this material before conservation decisions were made.

The use of pith paper as a painting support is specific to southern Chinese export art from the first half of the 19th century (Chassaing 2015). It is manufactured by cutting thin sheets from the inner pith of the plant Tetrapanax papyrifer, followed by reshaping with water. Past research has shown that after drying, the material becomes brittle and may dramatically change in dimension if subsequently exposed to water, creating cockling splitting and cracking (Nesbit et al. 2010). This property of pith paper significantly shaped our treatment decision-making, as it limited the use of aqueous methods of mending and washing normally applied to paper objects.

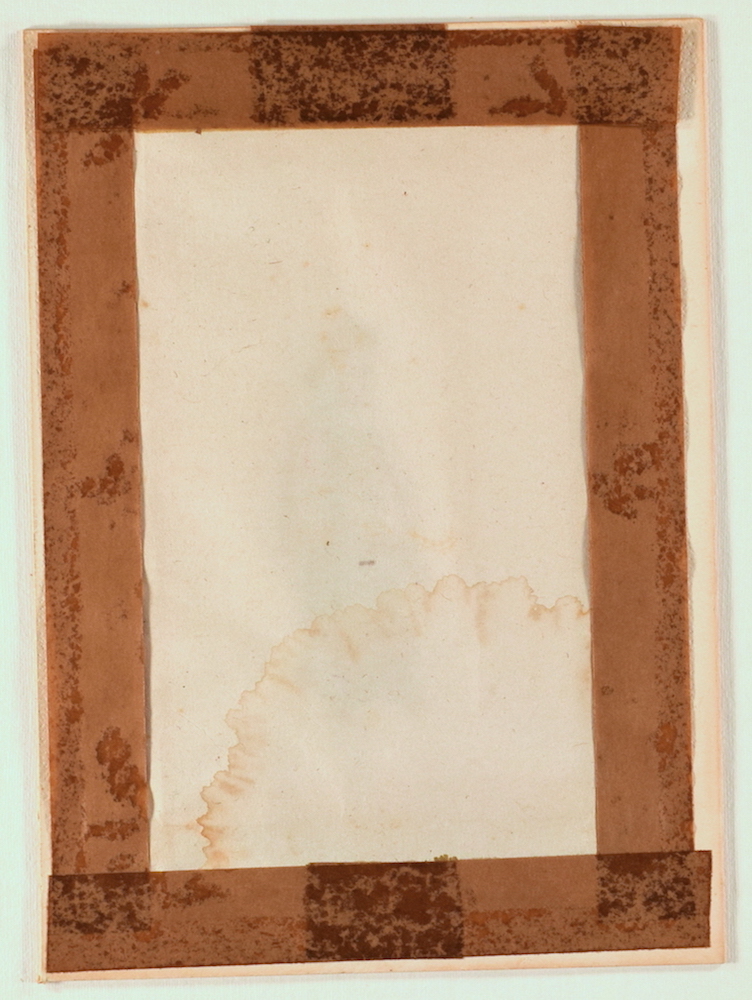

During an initial examination, the auxiliary lining paper and adhesive tapes used for framing the pith paper were found to be significantly deteriorated and structurally unstable. Based on the likelihood that all six paintings were in the same condition, increasing the chemical and mechanical stability of the paintings became the foremost treatment aim. As the paintings were part of a private collection, a treatment proposal was submitted to the client to ensure decisions were in line with stakeholder needs.

STEP 2: UNPACKING THE PAINTINGS

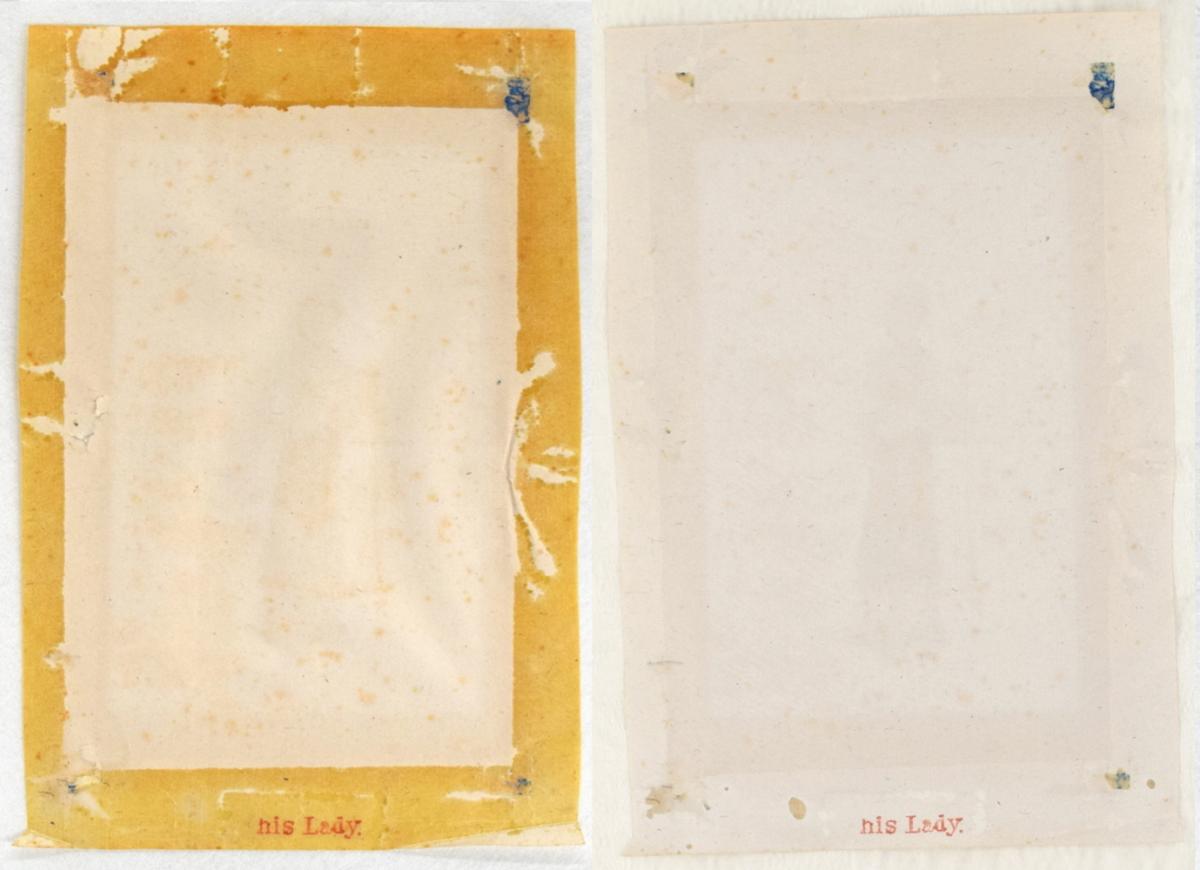

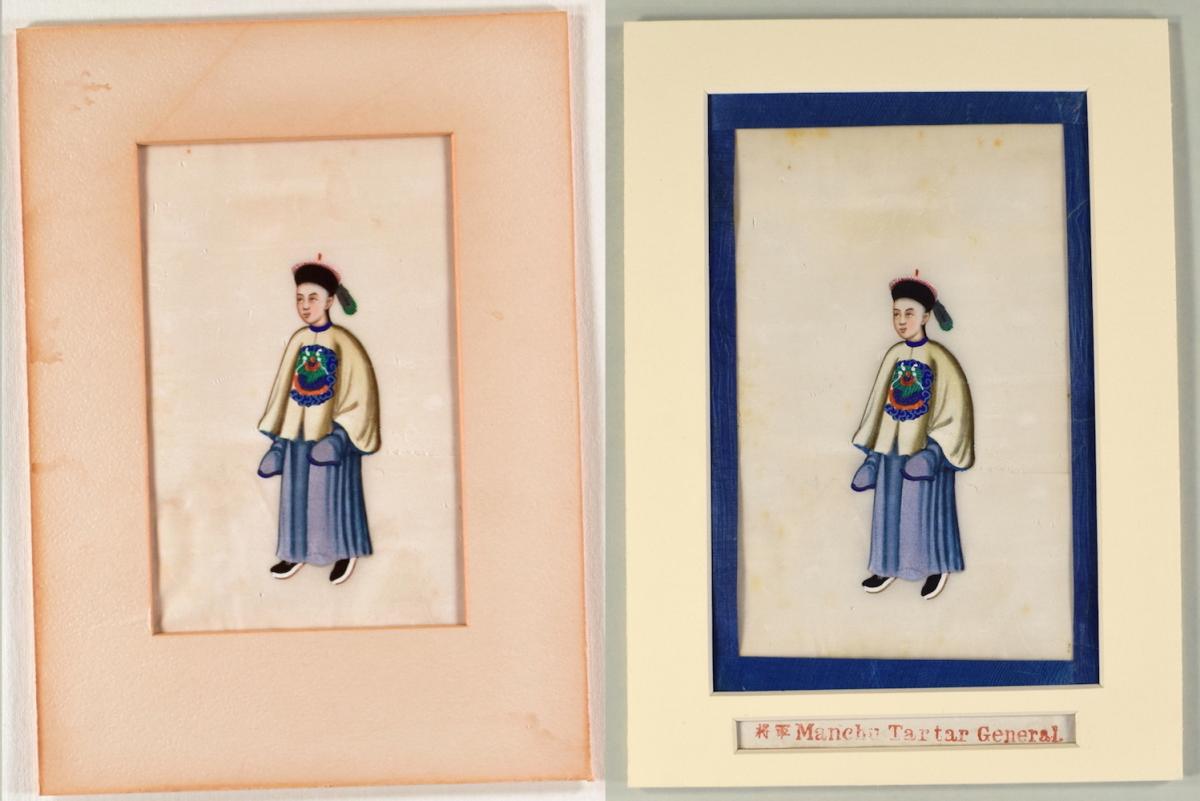

The framing materials were first separated from the supports to provide greater access to the inner layers. When the window mount was removed, a bright blue tape adhering the pith paper to the auxiliary paper was revealed. This tape was of historical interest, as it resembles the original silk ribbons used in the 19th century to mount pith paintings into collectors’ albums (Boone 2003). Red printed inscriptions were also found on the auxiliary paper below the paintings, providing identities and titles for the court figures depicted above.

Significant adhesive staining and discolouration of the auxiliary support strongly suggested a washing treatment. However, the moisture sensitivity of the pith meant that the paper needed to be removed before washing could occur. The highly cross-linked adhesive of the tape did not respond to multiple solvent tests, and finally mechanical removal with a scalpel was selected as the most effective and risk-averse technique for separating the materials.

STEP 3: TREATING THE AUXILIARY PAPER SUPPORTS

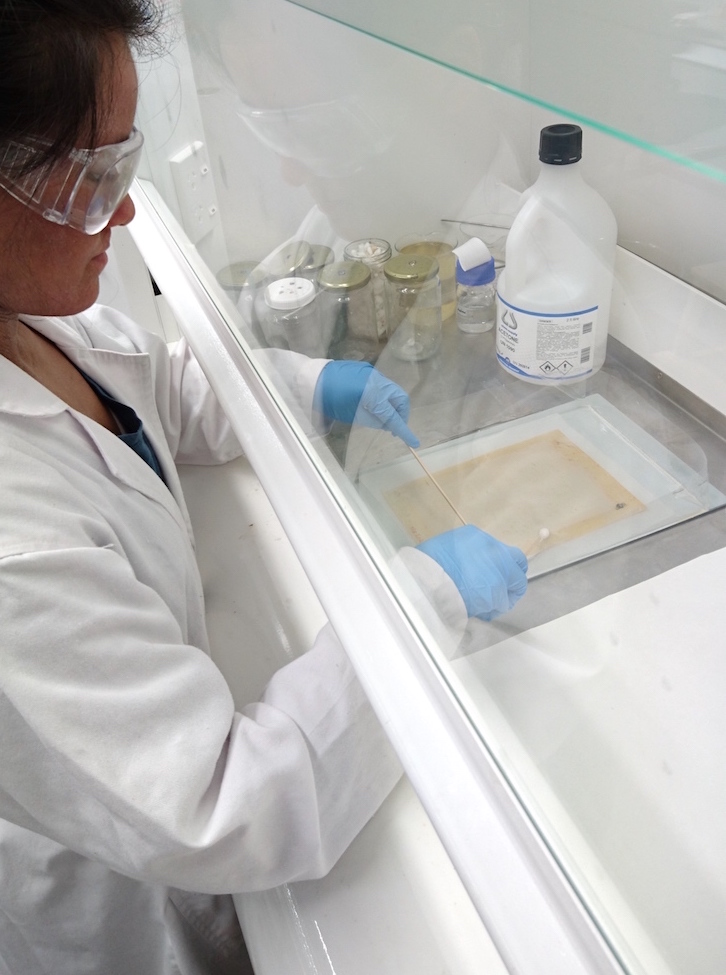

Immersion baths were selected to achieve overall stain reduction. After solvent tests on both the stain and ink media, the auxiliary papers were washed in acetone baths with significant visual results. Due to the toxicity of acetone, care was taken to protect personnel and fellow lab users from the fumes.

Next, washing in a water bath buffered with calcium hydroxide was undertaken to decrease the acidity of the lining papers and increased their flexibility (Harnly et al. 1990). A lining of Japanese tissue was applied to the verso of the paper support to strengthen its mechanical properties.

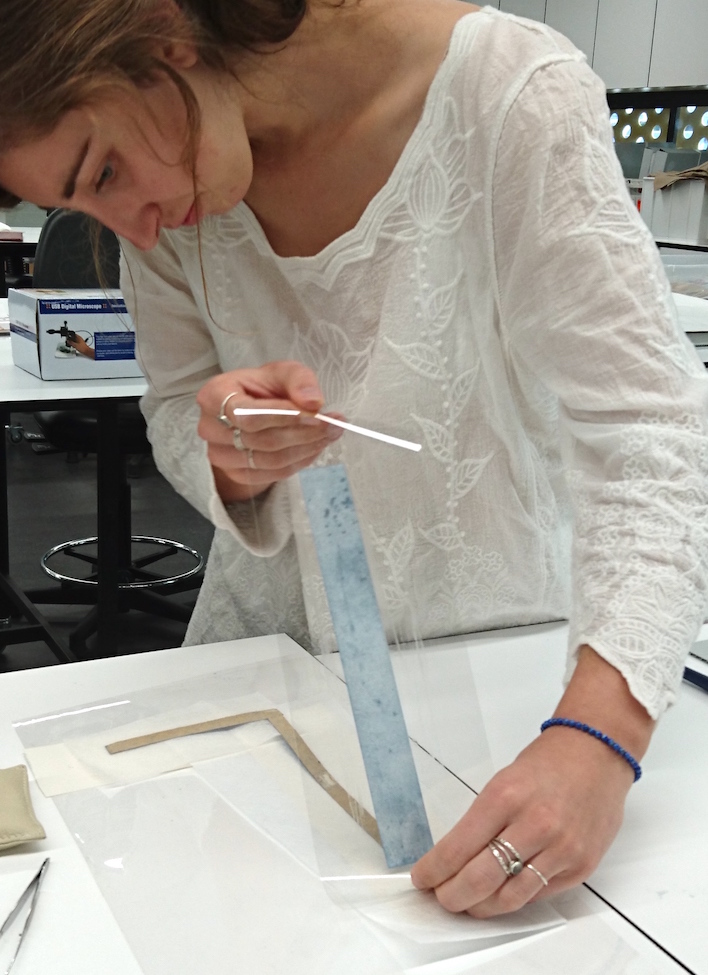

STEP 4: TREATING THE BLUE TAPES

During the mechanical removal of the tape, some parts of the tape carrier were torn, and the adhesion of the tapes had also been reduced. A lining of Japanese tissue toned with blue watercolour was used to reinforce the blue tape, and minor inpainting was used to disguise the losses for increased aesthetic unity.

STEP 5: TREATING THE PRIMARY PITH SUPPORTS

The primary supports were in remarkably good condition considering their inherent fragility, possibly due to the protective nature of the frames. There was little significant overall yellowing no large cracks or cockling; properties common in aged pith paper (Hasler 2015). Small losses and cracks were apparent along edges and in the majority of corners, most likely caused by stresses where movement of the pith paper had been inhibited by its adhesion to the blue tape. On releasing the pith paper primary supports from the blue tape strips, it was decided that all major points of weakness should be reinforced to reduce the likelihood of further damage. Small local mends were selected over overall lining as more sympathetic given the existing structural integrity and sound condition of all six pith papers in the collection.

There is comparatively little existing literature concerned with the application of local mends to pith paper paintings; the majority of documented treatments involve the overall lining of badly damaged sheets with light-weight Japanese tissue to improve structural cohesion and provide adequate support (Mendia Rios 2016). As lining creates an even amount of stress across the sheets, water-based adhesives, such as starch paste, can be used effectively without significant risk of warping or cockling (Mendia Rios 2016). This is not the case for locally applied mends, with distortion as a result of treatment undertaken in this manner not unheard of (Arpo 2000).

To minimise the proximity of the pith paintings to water, mending of the pith was carried out using a very light-weight Japanese tissue which had previously been wetted out with 2% Klucel G in distilled water and left to dry (Jenkins 2010). The tissue was then reactivated with ethanol prior to application (Holt 1999). A seam-like method of repair was selected for the mends (Mendia Rios 2016), with little rectangular pieces of Japanese tissue torn into shape and placed like band-aids across tears using tweezers, before being reactivated with a drop of ethanol introduced on the tip of a brush. This method provided adequate adhesion between the mend material and the primary support, while minimising stress placed on the pith paper and allowing for continued movement of the material in response to environmental fluctuations (Jenkins 2010).

STEP 6: REHOUSING THE PAINTINGS

As the original frame mounts covered the historically significant red ink inscriptions and blue tape which were discovered during treatment, a new framing layout with a reduced border and inscription window was suggested. The new mounts were made with archival board to ensure the long-term stability of the materials in direct contact with the objects, and the original wooden frames were reused.

The newly-reinforced blue tape window was hinge-mounted to the auxiliary support at two points along the right edge. Rather than adhering the tape directly to the pith support as before, this attachment technique allows for future dimensional changes of the pith.

CONCLUSION

In summary, each treatment step was carefully considered in terms of the advantages to the long-term chemical and structural stability of the paintings. Historically significant information gained during treatment not only increased the understanding of the objects’ story, but was also incorporated into the final rehousing choices. New techniques suitable for fragile and moisture-sensitive materials were learnt in the process of treating this remarkable collection of pith paper paintings.

Acknowledgements

Thanks must be expressed to the client for her gracious permission to share this project with AICCM, and to supervisor Sophie Lewincamp for her invaluable guidance and support.

References

Arpo, M 2000, ‘The conservation of Chinese export paintings on pith paper’, in R Hordal & T Ruuben (eds), The Conservator as an investigator: postprints of the Baltic-Nordic Conference on conserved and restored works of art, 6-9th October 1999, Conservation Center, Kanut, Tallinn, pp. 77–84.

Boone, T 2003, ‘Preserving pith paintings’, Library of Congress Information Bulletin, May, accessed 30 January 2017, <https://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/0305/conserve.html >.

Chassaing, P 2015, ‘Pith paper used for Chinese export paintings’, Journal of Paper Conservation, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 90-97.

Harnly, MW, Mear, C & Ruggles, JE (eds) 1990, ‘Washing’, Paper Conservation Catalogue, AIC/BPG, Washington.

Hasler, E 2015, ‘Conserving Chinese pith paintings’, Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, 21 October, accessed 30 January 2017, <http://www.kew.org/discover/blogs/library-art-and-archives/conserving-ch….

Holt, JG 1999, ‘The repair of pith paper objects’, ICOM Ethnographic Conservation Newsletter, April, no. 19, accessed 8 March 2017, <http://anthropology.si.edu/ConservL/ICOMnews/N19/icom0499.htm#THE%20REPA….

Jenkins, P 2010, ‘Pith paintings’, ICON News, January, issue 29, p. 29.

Mendia Rios, G 2016, ‘Conservation of 15 Chinese pith paintings: an exotic ‘souvenir’ for European travellers’, Royal Museums Greenwich, 16 Dec, accessed 5 April 2017, < http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/behind-the-scenes/blog/conservation-15-chi….

Nesbitt, M, Prosser, R & Williams, I 2010, ‘Rice-paper plant- Tetrapanax papyrifer: the gauze of the gods and its products’, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 71-92.