From the 30th May till the 16th June of this year, I was fortunate enough to travel to the United States of America (US) to explore American and international conservation. My journey started with the 2018 AIC Annual Meeting in Houston, Texas and continued to the west coast of California where I visited as many conservation laboratories as possible. I learned many things (only half the conservators I met work in basements), connected with some incredible people and once again affirmed that I am in the right industry for me.

Challenging Conference Concepts

The 2018 AIC Annual Meeting followed the theme ‘Material Matters’. The conference began with over a thousand conservation professionals gathered together for the opening sessions, giving me a hint of how big conservation is in the US. Interestingly, all opening general session talks explored materiality in some unexpected ways.

Glenn Wharton kicked off the conference with his talk ‘Materiality & Immateriality in the Conservation of Contemporary Art’. With new artistic processes emerging, he asked what is the conservation object and posited the need to allow for artist’s desire for interaction (theirs or the publics) with the artwork when conserving it.

Carrie McNeal took our thoughts to the spaces in our conservation labs where terrible piles of stored ‘things’ abound that no one knows what to do with. She argues this is important and that we need to create a material culture of conservation. This would include documenting the history of our field, collecting our history and documents, and taking steps to preserve our own material culture (think of pigment collections). Everything from tools, instruments, mock ups, samples, aprons/lab coats/apparel, photographs (not documentation ones) and even previously treated artifacts are all important parts of conservation history.

Vanessa Applebaum took the discussion to very new materials entering museum collections – three dimensional (3D) printed objects. She covered 3D printing used in conservation treatments to create missing parts, as well as 3D printed museum objects. Challenges include the unknown chemical composition of the material, unstable nature, unpredictable degradation characteristics and rates as well as questioning what constitutes the object- the digital file used to create it, the physical object, or both. They used a case study of an exhibition titled ‘3D: printing the future’ where a Blueprint Pack allowed you to reproduce degraded objects or creating a travelling exhibition that was also paradoxically concurrent in different locations. Everyone could print their own, simultaneously replicating the initial display whilst printing your own ‘original’ one.

Lauren Sorenson and Crystal Sanchez in their talk, The Physical of the Digital, said we are all technologists and preserving digital work takes all of us. They also pointed out the materiality of our digital systems and the need for new ways of documenting what is generally known as the intangible.

Favourite Focused Sessions

I mainly explored the Book & Paper sessions due to my area of specialisation, but I also went to Collection Care, Photographic Materials and Problematic Materials sessions.

Day 1

Brook Prestowitz helped us understand Japanese paper that is also known as washi. Her detailed talk covered all the different fibre types and preparation, but more importantly drew attention to its importance. Three washi were listed as important Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2014. Challenges for washi include a language barrier, spelling variations, names that once stood for quality papers now being loosely used by manufacturers and difficultly getting materials. Younger generations are becoming less interested in the traditional craft of papermaking, toolmakers are disappearing and we are losing a lot of unique papers. Conservation needs to support the washi papermaking trade we are so reliant on.

At the end of Day 1 Elmer Eusman took us back in time with him as he looked back and took stock of former conservation projects he had the ‘fortune or misfortune of working on’. This included his student experience washing thirty 16th century Albrecht Dürer prints at once in a sink. Unfortunately, he accidentally punched a hole through a print with the delicate touch of one finger during a moment of inattention. Then he talked about his use of light bleaching on a 19th century drawing by Joseph Keppler. Light bleaching caused the paper to get darker, and then adding hydrogen hydroxide (water) led to sections turning a deep, dark brown. Luckily this led to him to a path to discover the manufacture process and justify to the curator that the discolouration was evidence of how it was made and so should be retained. After a dizzying array of disasters that he dealt with throughout his career with suitable aplomb (based on his accounts), he concluded by assuring us that everything was going to be alright.

Day 2

Kelly McCauley Krish and Jean-Louis Bigourdan evaluated using A-D Strips to detect other forms of acidic off-gassing. A-D Strips were originally created by the Image Permanence Institute to evaluate stage of chemical degradation of cellulose acetate film. The aim of their research was to determine if A-D Strips can successfully assess the safety of materials for museum objects. Testing revealed that A-D Strips compared favourably to the results of with Oddy coupons. Furthermore, they are inexpensive, quick and easy to use. Issues with using A-D Strips in this manner included not being able to detect lower concentrations (the A-D Strip scale was limiting), they only revealed the presence of acidic gases and results did not distinguish between the acids. They concluded that further research was needed.

Jennifer Hain Teper helped us understand how to manage expectations in Scrapbook Conservation Approaches. Scrapbooks are problematic, messy, overfilled with all kinds of ephemera and other poor quality materials including in some rare cases food. They present many challenges and are known as the book conservators ‘arch nemesis’ (nemesis appears later in the conference- stay tuned!). At the University of Illinois they have nearly 1,000 scrapbooks. Approaches to their conservation vary greatly and treatment at the University has in some cases taken upwards of 100 hours. Jennifer created a treatment guide with different levels of treatment specified with estimated treatment times to help conservators manage treatment plans and time.

Kathleen Mullen and Heather Heckman investigated ‘Cellulose Nitrate Film Decomposition and Associated Fire Risk’. Some literature states deteriorated cellulose nitrate film is relatively inert whilst other sources say it is shock sensitive and liken it to an explosive. This talk sought to highlight these disparities in literature and draw attention to the unproven link between decomposition and combustibility. Through conducting various tests they discovered: there is no quantifiable correlation between chemical behaviour and what you see with the naked eye, combustibility is dependent on the levels of nitration that remain – the less nitrated the material the less flammable it is (so it can indeed become inert), the brown powder from the last stage of degradation is neither friction or shock sensitive and the staged model of degradation (five or six stages depending on the literature your read) does not reflect the true nature of the film or its hazards. The session concluded with the room coordinator asking the audience if there were any burning questions…

Day 3

Day three began bright and early with the AIC Business meeting, attended by those that were tempted by the allure of bagels for breakfast and big discussions over coffee. The President Margaret Holben Ellis asked why conservators aren’t ‘automatically at the table to discuss any decisions or actions for cultural heritage’ and posits we can no longer be just behind the scenes technical experts. Brenda Bernier in the Communications Report stated that we need to present ourselves as creative problem solvers, people managers and thought leaders in the cultural heritage sector.

We then proceeded with the final day of talks. Chi-Chun Lin and Hsuan-Yu Chen got us to ‘Think Outside the Box’ with their talk on the proper mounting and conservation of a manuscript on toilet paper. Created in 1980 by a political prisoner during her imprisonment, the manuscript is written in ball point pen and presents many conservation issues. These include it’s highly hygroscopic nature, vulnerability, propensity to blow away with a breath of air and the need to maintain the toilet paper texture. Using principles of minimum intervention and reversibility, they experimented with friction and static electricity to create an appropriate mounting technique. Ultimately, friction combined with an angled support successfully displayed the toilet paper.

Would You Like Some Book & Paper Tips With Your Lunch?

The Book & Paper Tip Session was the first of its kind that I have attended. We sat back and enjoyed a leisurely lunch, only to leap in to action to snap a photo or take hurried notes as a series of practical, fantastic ideas were thrown at us in five minute sessions by over ten individuals.

We were shown how to

– Post-image process watermark photographs in Photoshop: improves examination and documentation, is simple, reproducible and easily accessible process

– Use agarose gel: to spot clean and effectively cast it into sheet form using Mylar

– Use 3 % gellan gum to reactivate adhesive pre-coated tissues: can be left for long periods of time with even swelling and without over-moistening (recommended you place tissue adhesive side up)

– Create re-moistenable tissue: paste out selected adhesive on Mylar sheet, place 1.6g Japanese tissue (possibly lightest tissue on the market and appears invisible over most media) on top, label Mylar, leave overnight to dry, cut out with required tissue with scalpel, lift with tweezers the reactivate with wetting solution that (recommended outing solution on glazed tile)

– Use shimbari (typically used in furniture conservation) to apply pressure on books during treatment: using solid fiber glass rods with vinyl endcaps on each end (inexpensive) in combination with a sewing frame or book cradle you can accurately place pressure exactly where you want it

– Encapsulate paper items using a soldering iron: the size of your encapsulation is only limited by the length of ruler you use and it is a cheap solution for those that don’t have access to required machinery

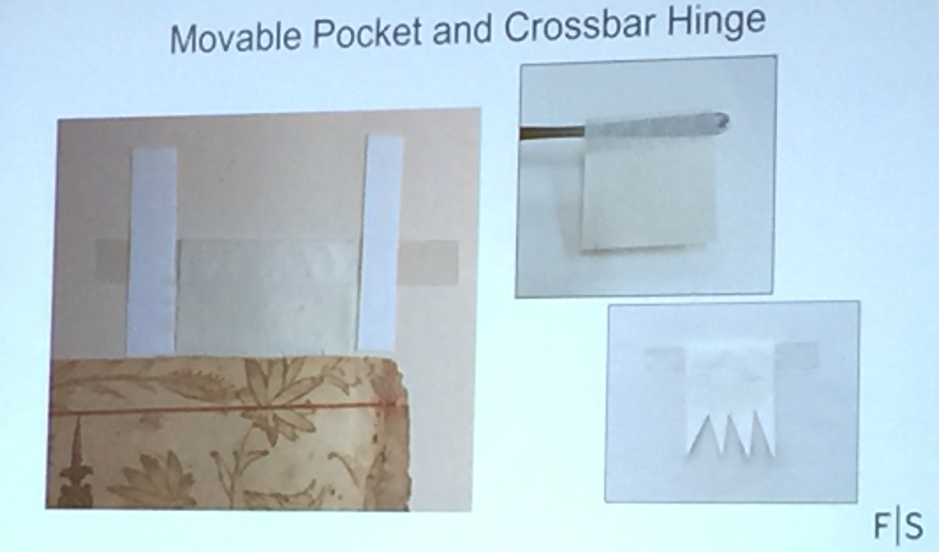

– Create movable pocket and crossbar Japanese tissue hinges: for flat paper items that need to be easily moved from different mounts, prevents the need to replace the hinges on the object and you can combine with an eyelash cut hinge.

– Unroll and temporarily install oversize paper works using a large metal screen (ideally mobile frame racks and magnets): allows photographic documentation, assessment and quick display. They recommended placing magnets 9-12 inches apart, using a team of people to hold the rolled work upright, apply the magnets and move the mobile rack to make the rack do the unrolling rather than the people.

Making Mistakes Matter

On the afternoon of the last evening we were all overloaded with information, inspired and ready to go home (in fact some people already were). However, AIC had one more thing in store for us. With a bar set up at the back, tables laden with food on the sides and a panel of mistake experts in the front we were welcomed to the last session of the conference titled ‘A Failure Shared is Not a Failure: Learning from Our Mistakes’. This was without a doubt the most heart-warming, heart wrenching session of the conference for me.

Lessons learned:

– Always look up

– Soluble nylon is not soluble

– Never start a treatment at 3pm on a Friday afternoon

– Deionised water is a powerful solvent

– A paint cross section is like an elephant

– Mistakes are ‘bound’ to happen in rare book treatments with a novice

– Always remember gravity

– Don’t test something then leave it for a day

– Our reactions to other people’s mistakes can affect that person for years and could change the course of (or even stop) their career

– Always have back up parts for your equipment to save time

– Leave an email trail to document decisions that go against your advice

– Ensure you have people sign off on documents that say the consequences of their decisions

– Make mistakes

– There are different kinds of mistakes

- First at the outset out of ignorance

- Then later when you become blasé and for some crazy reason something doesn’t go the way it has the countless times before

– Do post-mortem for objects after damage is done

– Finish your treatment before you start drinking beer

– Every few years you will have to match wills with an object that doesn’t want to be conserved and that object will have a name. This name is nemesis. Multiple objects can/will/have been your nemesis- be ready for the next one.

Traversing the Conservation Labs of California

After Texas, I went west to soak up the sunshine and visit conservation colleagues in their local habitats. I started in Los Angeles, exploring three conservation labs and then went on to San Francisco where I visited another two conservation labs.

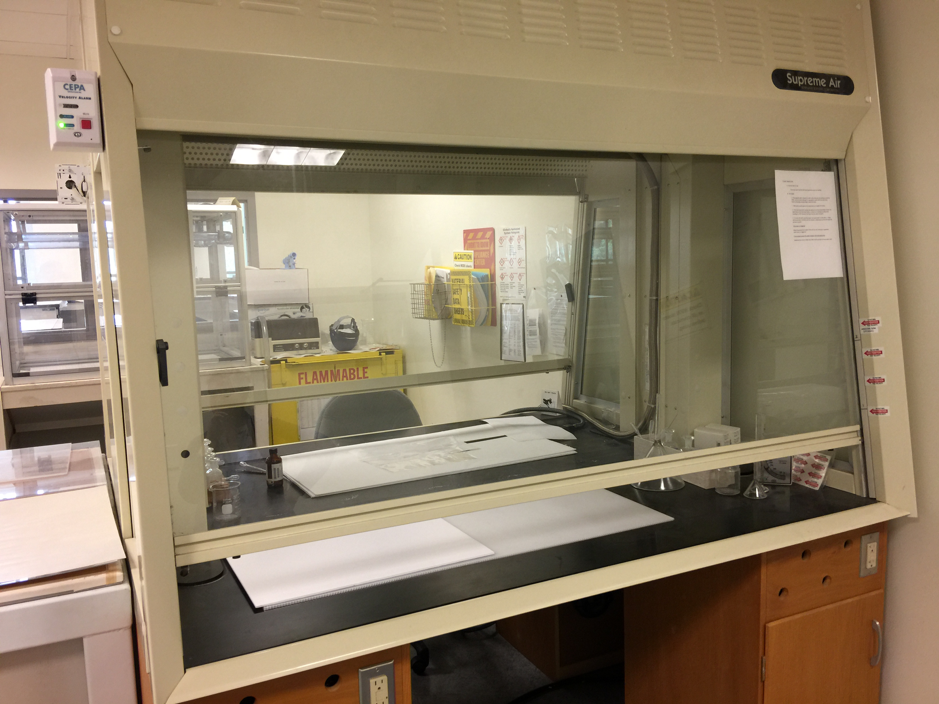

The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens is primarily a research based library with large exhibition spaces. I visited the book and paper conservators and was shown around their luxuriously huge conservation laboratory on an upper level of the building with large windows. They appeared somewhat embarrassed by the space (it’s at least three times the size of the conservation lab at the National Maritime Museum for a space comparison). I fell in love with their double sided fumehood that they had created from two separate fumehoods. They also had a whole room dedicated to washing and chemical use.

The Getty Research Institute is part of the Getty Centre and sits on a hill overlooking Los Angeles. The Research Collection numbers in the millions. I visited the Paper and then the Audio Visual Conservation Laboratory. They had vertical storage for materials with vertical shelf dividers on diagonals. These vertical stores were great space savers and storage solutions.

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art has a relatively small Paper Conservation Laboratory where the Paper Conservator and a Mellon Fellow work. However, they managed to fit equipment for light bleaching and an incredibly huge air mattress press designed for drying and pressing large works without changing the surface characteristics of the paper. They had fantastic object underneath signs that included celebrities and cute animals!

The San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park and Museum is part of the National Park Service which is the second largest collection in the US (after the Smithsonian Museums). I first went to the Library and attached bindery to chat with the conservators there. Most of our conversations were about cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate. I learned of their centralised offsite storage facility for cellulose nitrate that is for all the National Park Service collections. From there I went to talk to the two conservators that looked after the Museum collection. My visit corresponded to when they had just discovered some severely deteriorated plastics in the store and were beginning a project to explore the plastics in the collection.

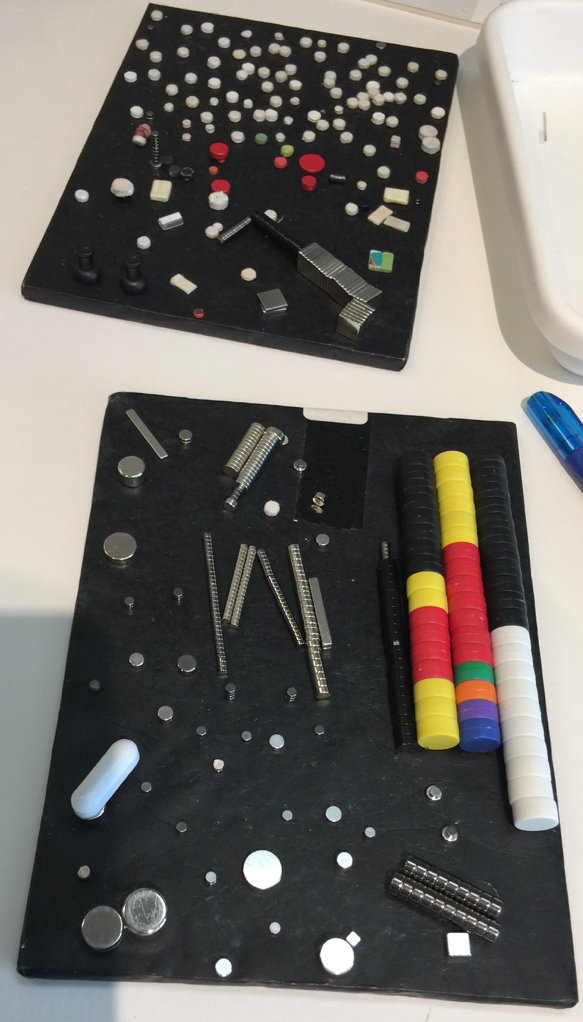

The Legion of Honor is part of Fine Arts Museums San Francisco and linked to the de Young Museum. The Paper Conservation Laboratory is located at the Legion of Honor and looks after over 100,000 paper items. The other specialist conservation labs are located at the de Young. I met with the Paper Conservator and Mellon Intern. They showed me their clever use of magnets to display books and combining these with pins to allow books to seemingly ‘stand’ on their own. They usually cover the magnets with Japanese tissue paper then either paint them or digitally print the part of the object that is underneath the magnet to make them appear invisible. Choosing the right size, shape and strength of magnetism was emphasised.

I discovered during my journey that going straight to a conservation conference after two flights from Australian is not ideal and that visiting two conservation labs in one day is a bit ambitious (especially when they are on opposing sides of LA). However, I wouldn’t change any part of my trip. I’m incredibly grateful to all the conservators that gave me their time and access to their conservation laboratories. They all seemed to love the very Australian Tim Tams I brought. My time in the US was a whirlwind of conservation adventures and I am excited to put in to practice what I have learned. I cannot wait to go back!