The Big Picture workshop focused on the unique challenges in the presentation, display, and collection care of large contemporary photographs. Over four days in June, 18 participants from a variety of public institutions and private practice, mostly US-based, gathered to discuss issues related to the preservation and conservation of large-scale works. To my surprise and delight, I was offered a place which, thanks to the generous support of my employers, State Library Victoria and Grimwade Conservation Services, I was able to accept.

The first day was devoted to case studies presented by conservators, as well as a curatorial overview. Lee Ann Daffner, Andrew W Mellon Conservator of Photographs at MoMA, opened her talk by claiming ‘We don’t have all the answers,’ which given her years of experience I found equally confronting and reassuring. She spoke of various issues surrounding several large-scale photographic works in the collection, the most memorable being Jeff Wall’s light box constructions, which present a printing process and presentation method that are both complicated, involved and increasingly difficult to replicate. They pose many conundrums due to the different components. For example, supply issues with light bulbs are being averted by stockpiling two spare sets per work, but some are no longer made. In the light of the case studies presented, I took Lee Ann’s frank opening statement to be a modest assessment of the activities of her department who continue to find a precarious balance between artist intent, aesthetic appreciation and preservation.

Peter Mustardo, co-founder of The Better Image, presented the perspective of private practice. Handling issues and mounting faults are the most common problems that he encounters with large contemporary works. Distortions in plane are regularly encountered, often due to poor mounting. For flattening, several key factors are required—space, staff, materials in sufficient size, equipment and a choreography that has been pre-visualised. Peter’s humidification set-up is familiar to most dealing with paper or photographs though his chosen product for the moisture source is a reusable PVA material called The Absorber®, which has a uniform, sponge-like pore structure that enhances capillary action. For drying and flattening, matboard, acrylic and weight are used, holding back on the first cycle and then adding more pressure on the second and third cycles. Conservators at The Better Image also use a vacuum heat press made for mounting posters for flattening RC prints. Heat is used to soften the support, and pressure to reform it into plane. Matboard is used on either side of the print, which is placed within a sleeve of thick silicon release paper. The platen is heated and the vacuum activated, then the heat is turned off and the print cools under constant pressure by maintaining the vacuum before transferring to pressing tables.

Two other fascinating case studies on this jam-packed first day deserve mention. Nora Kennedy, Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge of the Department of Photograph Conservation at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, presented the challenging task of displaying Blueprint for a Temple,1980, by Francesca Woodman, a diazo collage, 2.7 x 4.2m in size, composed of 29 pieces involving layering, irregular edges and a secondary support. Not a lot of information was available when it was first installed in the year of its production. As the artist was deceased, her parents represented her intent, wanting the display to impart an ‘informal spontaneity’. The mounting was complicated, involving a glassine tracing and a combination of pull-through hinges, double-sided tape and magnets. A gantry was necessary, and a magnetic field viewer was handy for locating the magnets. Nora remarked that the system they came up with would probably not be replicated again, and is purely specific to this artwork. Krista Lough, in private practice, spoke about Deana Lawson’s Assemblage, an installation of 700 photographs that the artist sourced from research online and are printed specifically for each installation using typical ‘drugstore’ materials and technology, in this case dye diffusion thermal transfer (D2T2). They are taped to the wall and the artist was happy for conservation to determine the best tape for this purpose. As they are printed for each installation, this choice was initially not guided by preservation or removability factors; however, during the course of the installation process the work became a collection item, and Krista has vowed from now on to factor in this possibility.

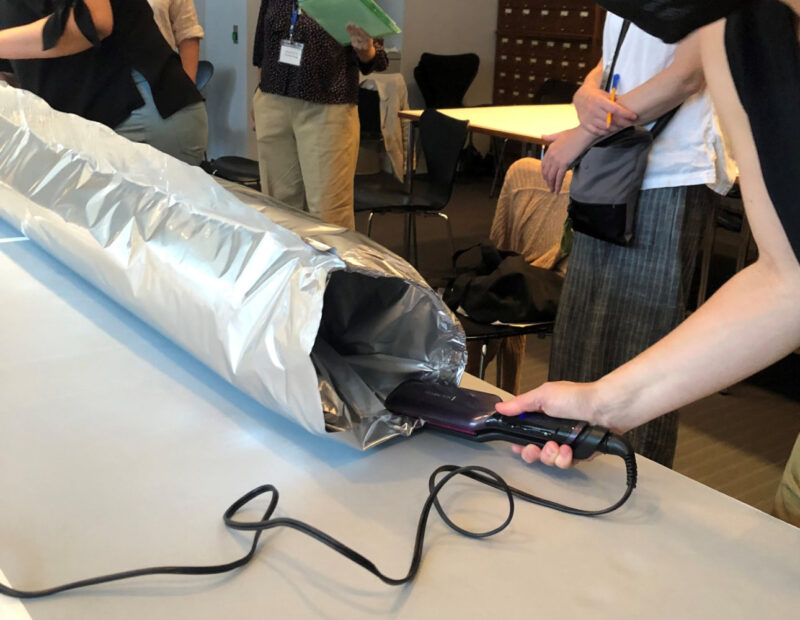

Day 2 began with a demonstration of vacuum rolling for cold storage by Meredith Reiss, Collections Manager, and Katie Sanderson, Associate Conservator, from the Met. These two were a dynamo team, and having undertaken this process many times the ‘choreography’ was honed to the finest degree and they almost wordlessly (except for explanations to the audience) executed the steps to achieve a smoothly interleaved, rolled print in a vacuum-sealed package. Most items in cold storage at the Met are rolled and packaged in a way to remove as much air (ie, moisture) as possible. They use a standard 10-inch diameter tube that is covered in Mylar adhered with P90 Plus tape (thinner and tackier than P90). A layer of Phototex is then wrapped around the tube and tucked in at the ends, secured with P90 Plus. Chromogenic prints have a Phototex interleaving but this is too abrasive for ink jet prints, especially if they are matte, in which case a plastic film is preferred. Dartek, a nylon film, is an option, but this holds 20% moisture. Marvelseal 360 is the final layer, acting as a sealable vapour barrier. Two ‘socks’ are created, one of which is wrapped around the tube, and the other placed inside. They are tucked and sealed at the ends, matte sides together, leaving a hole from which air can be vacuumed out and finally sealed. A hair straightener is the device used to provide the heat for the seal—apparently a 3am lightbulb moment from one of the interns.

Next, Sylvie Pénichon, Director of Photography and Media Conservation at the Art Institute of Chicago, presented a comprehensive review of mounting substrates. Sylvie advocated for the use of the Photographic Information Record (PIR), the artists’ questionnaire form that was designed and vetted by an international committee of conservators with input from curators and collections managers. We then launched into a Cold Storage Panel, with snapshots of the set-up offered by representatives from MoMA, the Getty, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Met. Each presented a very sophisticated set-up, from my point of view, but told tales of constant campaigning over several years preceding installation, restricted involvement from conservation over specifications, some facilities being now near capacity, and sustainability becoming a greater focus.

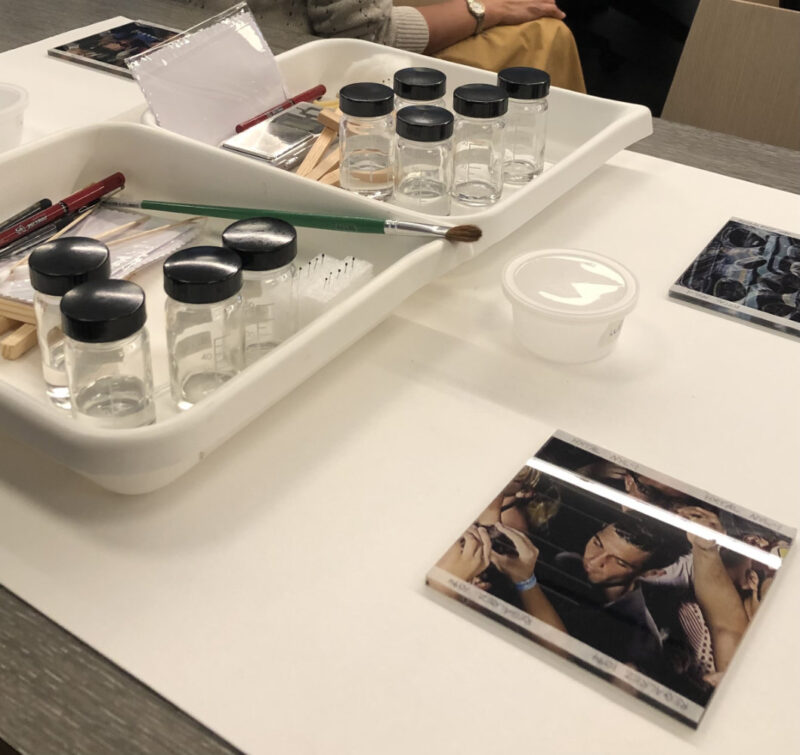

Day 2 concluded with a hands-on session tackling the repair of scratches on PMMA. Anna Laganà from the Getty Conservation Institute presented a lecture and demonstration via Zoom, while Sarah Freeman from the J Paul Getty Museum was available to demonstrate in person and assist us as we all had a go. A small kit was provided with a scratched and chipped face-mounted photograph for practising, two mini detailer synthetic sable brushes (Princeton Series 3050R, round, #20/0), a set of stainless-steel insect pins and a spectacle cloth.

Extensive testing led to Regalrez 1094 for chips and Hxtal NYL-1 for scratches as the preferred resins, detailed in Laganà and Freeman’s article ‘Repairing transparency, recovering the image. Research and testing fill materials and methods for conservation treatments on photographs face-mounted with poly (methyl methacrylate)’, presented at the 2019 AIC PMG & ICOM-CC PMWG Joint Meeting in New York City.

On Day 3 we had the privilege of hearing artists who tend towards large-format photography speak about their work, including Tina Barney, Vera Lutter, Richard Learoyd, Lola Flash and Mariah Robertson. Each is fairly committed to analogue processes, some resorting to stockpiling the materials and chemistry of discontinued stock, also exploring unconventional means of capturing images. Lutter at one point used her apartment as a camera obscura, projecting inverted images of the outside world onto large sheets of photographic paper, while Robertson creates camera-less abstractions, exposing whole rolls, 100 feet or more, of paper. Committed to the visibility of LGBTIQA+ and communities of colour, Lola Flash works in large scale to make the unseen seen, ‘the bigger the better’, seeing size as a demand to ‘give me my space’, while Tina Barney uses scale so the viewer can see every detail, creating a space that is believable and able to be shared.

Two field trips featured in the program—from Grand Central Station we travelled to Mount Vernon to visit Hank’s Photographic, a photographic studio that specialises in black-and-white printing on fibre-based paper, owned for over 35 years by Steve Rifkin. The darkroom and processing lab are custom-built and can accommodate sizes up to 8 x 10 feet and we were lucky to witness the exposure and development of a yet-to-be-released large and stunning print by Richard Learoyd. Joe Hartwell demonstrated dry mounting of a photograph, defying dust and dents, he said ‘The secret of the process is to be obsessed’.

The next day we travelled by subway to Queens to visit the storage facility for MoMA. The building is 94,000 square feet and at 90% capacity due to the ambitious acquisition program. Many large works are stored within handling frames in rolling tills. The structure provides airflow rather than creating a microclimate. During the visit we were shown many large photographic works and discussed their complex storage needs.

The final session of the workshop was devoted to discussion regarding reprints and exhibition copies of photographs. We heard the perspectives from various museums—MoMA, the Art Institute of Chicago, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) and the Guggenheim. By the 1980s, MoMA had a policy of acquiring a second print of colour works, placing both in cold storage. One is available for exhibition and loan; the other is kept as a backup until such time as the first is judged to have faded significantly. This solution helps resolve the conflict between the goals of preserving the collection and making it known through exhibition and loan. The other museums have variations on this policy, which must be revisited every few years to assess the capacity of an institution in terms of cost, space and time. Photography is a medium in which infinite multiplicity is possible, so reprinting has become a preservation strategy for colour works so vulnerable to damage and so difficult to successfully repair. Respect for the artist’s intent and clear documentation are both paramount. This topic inspired an animated discussion, which will no doubt continue. For those interested, SFMOMA hosted a reprinting symposium in 2019 and all the talks are available on the website

As I have only touched on the content presented during the workshop, please get in touch if you would like further information or access to the online resources that were provided.