This report details the cleaning treatment pathway for an early 20th century papier-mâché frame in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW). This process was undertaken during an internship at AGNSW in July 2018 under the supervision of Head Frame Conservator Margaret Sawicki.

The Frame

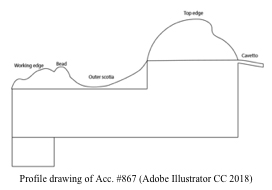

Believed to be the original frame for Sydney Long’s Hawkesbury Landscape (c. 1925), this papier-mâché picture frame presented a unique opportunity to become familiar with material types that differ from traditional gilding, timber and composition. The frame was in a stable condition, but the entire surface was covered in a thick bronze overpaint and clear varnish that obscured the original finish. The original finish is bronze paint, most probably a wax-based bronze powder, on an imitation red bole foundation.

Investigation

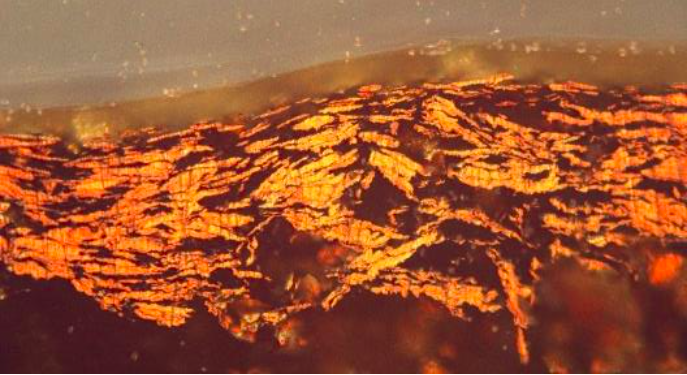

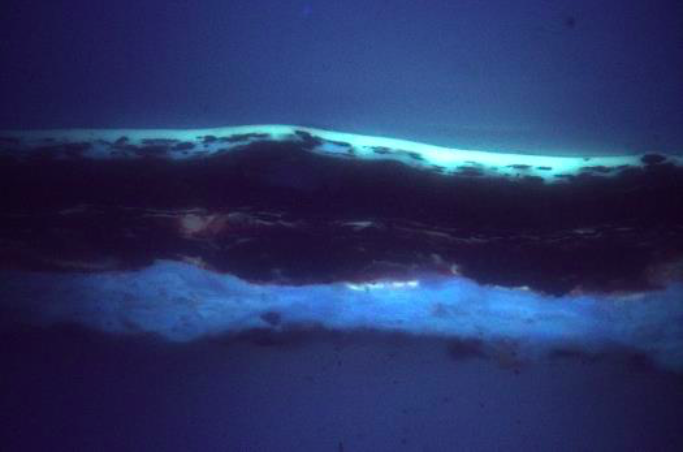

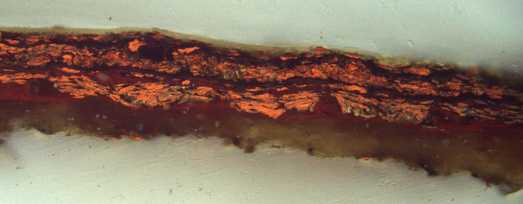

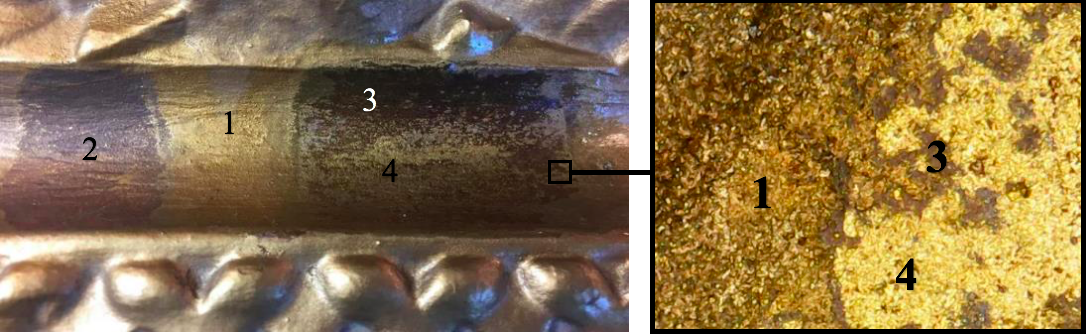

In order to investigate the thickness of the overpaint and determine the original finish, a series of cross sections were prepared. Some key observations on the stratigraphy were made;

- Confirmation of a clear varnish coating across the surface on both samples. The bright white/green ultraviolet fluorescence of this coating suggests cellulose acetate or cellulose nitrate (Rivers and Umney 2003, p. 610; Simpson-Grant 2000).

- There are multiple layers of degraded and discoloured bronze overpaint on a foundation of red.

- The violet/white ultraviolet fluorescence of the papier-mâché indicates the presence of animal glue and/or gypsum (Rivers and Umney 2003, p. 610; Stuart 2007, p. 77). These are common materials used as binders and fillers that suggest a pulped papier-mâché method of production post 18th century, also known as Carton Pierre (Wetherall 1991, p. 26).

- The lowermost bronze layer has a platelet structure (lamellae) indicative of the grinding down process from leaf (Lins 1991, p. 21). This suggests that the original surface finish is genuine bronze powder (Thornton 2000, p. 312).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and solubility testing was also performed. Results from these tests indicate the presence of nitrocellulose and shellac-based paints, indeed confirming the thickness and complexity of the surface stratigraphy!

Gel Cleaning

Due to the thickness of the overpaint, the project presented a good opportunity to test the efficacy of gel cleaning on 3 dimensional objects! Three primary types of gel systems were tested; Xanthan gum in acetone, Pemulen™ TR2 in benzyl alcohol with EDTA and Polyvinyl alcohol Borax gel in acetone.

The Pemulen™ TR-2 gel was most effective at removing the clear coating and first and second layers of bronze overpaint. The results indicate that 50-60 minutes was the optimal working time, before scraping off the gel and swollen media using a spatula.

The Xanthan gum-acetone system was least effective and unable to soften the first layer of bronze overpaint. The viscosity of the solution also made it difficult to clear, particularly from within the interstices of the ornament. In contrast, the Borax gel could easily be peeled away and reused. This film structure made the material highly controlled and was particularly useful in flat areas of the frame. However, the rigidity of the material rendered it unworkable for more structured areas.

![Figure 9: After cleaning [bronze overpaint removed], acc. #867, 12/07/18. Figure 9: After cleaning [bronze overpaint removed], acc. #867, 12/07/18.](https://aiccm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Screen-Shot-2018-09-15-at-11.00.26-am.png)

Proposed pathway:

Flat areas (outer scotia, cavetto); Pemulen™ TR-2 gel [scraped, cleared] to remove clear coating and first two layers of overpaint. Third layer to be softened using Borax gel and removed using scalpel.

Ornamental areas (working edge, top edge, corners); Pemulen™ TR-2 gel [scraped, cleared] to remove clear coating, and first two layers of overpaint. Third layer to be softened using benzyl alcohol or acetone and removed using scalpel.

“All that glitters is not gold” (Thornton 2000, p. 307).

This investigation has reiterated the complex nature associated with frame finishes, where a lack of gilding certainly doesn’t translate to a lack of surprises, challenges and problem solving. This decision-making process offered invaluable experience working with uncommon materials such as papier-mâché and enabled an investigation that employed modern conservation ethics and techniques. Experience forming and working with gels on 3-dimensional objects, as well as the opportunity to practice analytical skills in FTIR and microscopy, was particularly wonderful.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Margaret for her commitment to my learning and development. Your generosity and willingness to share your knowledge is inspiring, and your genuine enthusiasm towards the field of frames has made this both a fun and invaluable experience.

Bibliography

Lins, A 1991, ‘Basic Properties of Gold Leaf’ in D Bigelow (ed.), Gilded Wood Conservation and History, Sound View Press, Madison, pp. 17-23.

Rivers, N and Umney, S 2003, ‘Conservation of Furniture’, Butterworth-Heinemann, Burlington.

Simpson-Grant, M. 2000, ‘The Use of Ultraviolet Induced Visible-Fluorescence in the Examination of Museum Objects, Part 2’,Conserve-O-Gram 1/10, viewed 12 July 2017, <https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/01-10.pdf>.

Stuart, B 2007, Analytical Techniques in Materials Conservation, Wiley, Chichester.

Thornton, J 2000, ‘All that Glitters is not Gold: Other Surfaces that Appear to be Gilded’ in T Drayman-Weisser (ed.), Gilded Metals History, Technology and Conservation, Archetype Publications, London, pp. 307-318.

Thornton, J and Adair, W 1994, ‘Applied decoration for historic interiors preserving composition ornament’, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Washington.

Wetherall, J 1991, ‘The History and Techniques of Composition’in S Budden (ed.), Gilding and surface decoration, UKIC Restoration Conference, 16 October, London, UKIC, London, pp. 26-29.